How the Avocado Fridge Came to Embody the '70s

In Depth

The phrase “midcentury kitchen” conjures an array of images, each more dazzling than the last: Needlessly complex gadgets designed to appeal to technoptimistic Americans of the 1950s! Formica in a bewildering array of colors! An outrageous landscape of avocado and—heaven help us—harvest gold!

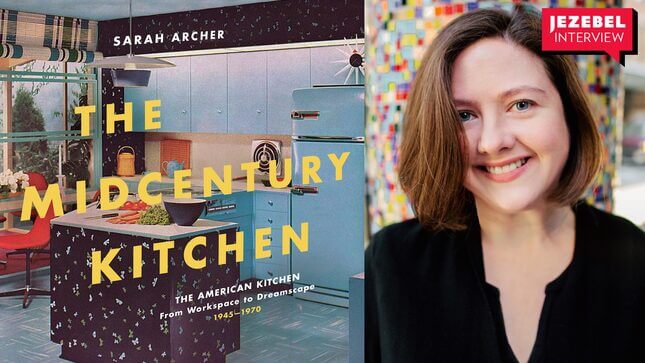

The Midcentury Kitchen, a new book by Sarah Archer, unpacks some of those remarkable, ridiculous features and explains how they came to be, tracing the transformation of the kitchen from a functional place for labor that sometimes wasn’t even its own room to a hip family hangout space. With lots of lavish illustrations, it’s also a great, Ozymandias-like opportunity to ponder how the modish kitchens of our current era will fare down the line. Look upon my subway tiles, ye mighty, and despair.

Back in December, author Sarah Archer helpfully explained what aluminum Christmas trees had to do with nuclear fear—mostly nothing, it turns out, despite the suspicions of the Jezebel staff, but they were very much a product of the Atomic Age. So I was curious to get her take on the many peculiarities of the midcentury kitchen, especially the absolutely baffling decision to install so many appliances in shades of avocado and “harvest gold.” She explained all that and more in a brief interview.

JEZEBEL: We think of the midcentury kitchen as being full of fads, some of which I will ask you about later. But I’m curious about how kitchens became subject to fads. I assume—and maybe this is a wrong assumption!—but I assume in the 19th century, you bought a heavy-duty cast iron stove and then you practically had to tear down the house to get rid of it.

SARAH ARCHER: It’s a combination of increasing homeownership in the postwar period, for one thing, which got people shopping for things and decorating on their own in a way that they hadn’t before. But it’s also because the kitchen really transformed from being a workspace into a living space. Although there had been a movement toward that in the ’20s and ’30s—advertising early refrigerators as though it were this invisible housekeeper who would make your glamorous life even easier and more glamorous—it was the ’50s and ’60s when a mass majority of people can afford what we think of as the standard appliance-packed kitchen of today. There was so much that changed in the way people cook and the way people get utilities from the outside world—everything from gas stoves to refrigeration, all these things that require gas and electricity and running water—it spruced up the bathroom to some extent, but it really transformed the kitchen. All those things that became standard by the 1930s converged there.

It was a natural place for manufacturers to look at their marketplace and, especially in the postwar period, to say, we’ve got lots of women who are back home now that men have returned to the workforce and lots of brand new homeowners who want to potentially entertain in their kitchen, and we can cultivate this idea that the kitchen isn’t just a place for you to get household work done, it’s a place for you to hang out. That was a brand new thing for people to market. That had never been something that was considered desirable, but suddenly it was.

We can cultivate this idea that the kitchen isn’t just a place for you to get household work done, it’s a place for you to hang out.

I think that the faddishness comes as a combination of Cold War optimism about new technology and, you know, Wow, think about all the things that have happened between 1920 and 1950. What amazing things will happen between 1950 and 1980? And basically, the only thing that happened is that appliances became beige. But for the generation that lived through all those changes and were old enough to remember coal stoves and not having running water to then have a dishwasher, it was really pivotal. I think the fads were really, at the time, not seen as fads. There was a general sense of, how will our lives be drastically transformed?

I was wondering if you could talk a little but more about how that shift from workspace to living space happened. Because I think about watching HGTV now—theoretically, its a space where you do things, but the whole open floor plan kitchen reveal revolves around the family hanging out and how we’re going to entertain.

It’s become basically the hub for entertaining. It’s partly that the nature of the room itself changed. But it’s also that society changed. We have this tendency, incorrect though it may be, especially nowadays, to think of everyone as “middle class.” Everyone is a version of people living in a reasonably nice dwelling, it’s not over-the-top crazy and it’s not terrible, and you’ve got a kitchen and you’ve got all your appliances. Then people who are super wealthy will translate that into an ultra-deluxe version, where you have maybe gorgeous marble soapstone countertops. But essentially, that’s a souped-up version of that 1950s, 1960s middle class hangout space.

What amazing things will happen between 1950 and 1980? Basically, the only thing that happened is that appliances became beige.

Before that, really before the Industrial Revolution, but up until the pre World War I era, there’s the saying that you either had help or you were help. There was not a huge population of middle-class people. There were a lot of people who lived in very, very modest dwellings, either farmhouses or tenement apartments in big cities. Especially with the big wave of immigration at the turn of the century, they may live in a single room with a stove, and that was their only source of heat; they may or may not have had running water. The “kitchen” was basically just the apartment. There wasn’t a discrete room for a lot of people. That was true for farmhouses, as well. And if you were well-to-do and you had household staff, which was more common among people we would probably characterize as upper middle class now, if you had live-in help, that was their workspace. It wasn’t an entertaining space.

Once appliances start getting marketed to this emerging middle class population of consumers beginning in the 1920—which is then thwarted for a couple of decades because of the Depression and the war, then bounces back really full force in the 50s and 60s—they’re essentially marketing a new kind of machine to a new kind of person. It’s not that all the rich people in the United States suddenly stopped having help and said, Oh, I have a fridge now! People who had staff still had staff. But it was more that you had this emerging bourgeoisie that thought, Oh, I can actually entertain, and it’s almost elegant, as though I were this very well-to-do person with staff, except it’s a fridge or it’s a stove or it’s something that will make that process automatically easier. That becomes this sort of cult of domesticity that takes hold in the atomic era, with this real focus on kids and their education and having cool interactive playtime and all that stuff that you can read about in Alexandra Lang’s wonderful book, The Design of Childhood, that becomes super-powered with the kitchen as kind of a hangout space and a workspace.

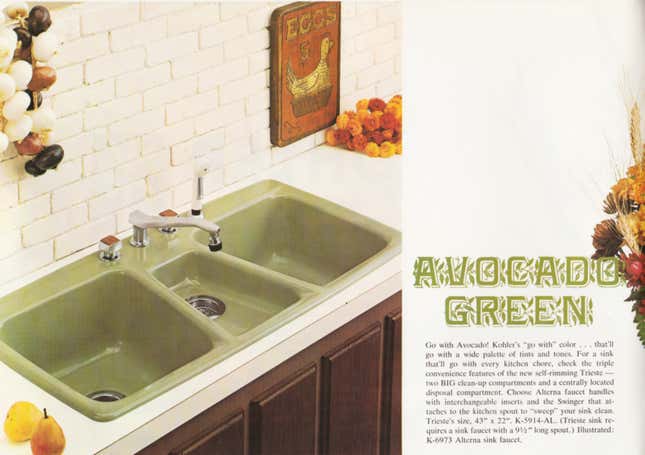

So, here’s a question: Why avocado? What was up with the avocado kitchen?

Which is a question that has vexed people for decades! Anyone who renovates an old fixer-upper, very often you’re ripping out some harvest gold or avocado appliances.

We tend to associate these colors with the ’70s, that’s when they were in full flower, but they were starting to appear in sales brochures and magazines as early as the ’60s. I don’t know if there is one distinctive reason why it was so vastly popular, but I can say companies went all-in on avocado. There were huge magazine spreads, advertisements, editorials, presenting this as the cool new thing, and they were often accessorized with nifty hanging plants and macrame holders, and women would be wearing these cool minidresses, so it was very much of a piece with the fashion of the era.

Companies went all-in on avocado.

And my theory about this—I can’t guarantee that this is true for everybody—but looking at the 1950s, when a lot of the appliances were pastel, what we think of almost as baby colors, pink, pale blue, pale yellow, all of those almost cake colors, there was a sense in the 1960s, especially in the last half of the decade, that all of that stuff was deeply uncool. It was what your parents may have had and it represented this suburban, almost conservative way of designing and decorating, this World’s Fair schtick, and now we’re going to be cool and have colors that reference the handmade, the natural. There started to be refrigerators that had woven rattan as a covering. Then the avocado becomes almost like the way fermentation is cool now. It’s a little bit au naturel, tethered to the hippie movement—harvest gold looked a little bit like straw—and it was new and it was a big swerve away from the candy colors of the ’50s.

So it is literally like reclaimed wood is now, where we’ll put this “natural” thing in this super modern kitchen.

Absolutely. It’s a precursor to borrowing elements of a real old-school look and then updating them. The rattan refrigerator is a perfect example, because it’s slapping this “handwoven” material on a machine. It’s still a machine! But it gives you the look and feel. You know, we’re in the macrame decade, so everything has got to fit in with that. The ’50s had been all about the future, and what will the future bring, and technology and exploring space. Those later decades, there’s a lot less of that. There’s more of a focus on questioning the nuclear family and living on communes and exploring different ways of living, not so much this obsessive focus on, like, The Jetsons.

And the answer is, basically, that it’s kind of the same. The kitchen nowadays is really almost shockingly not that different from the kitchen of fifty years ago.

I wanted to ask you specifically about one of my favorite pieces of consumer culture ephemera from the ’50s, which is that video, a musical about General Motors’ subsidiary Frigidaire where a dashing mystery guy whisks the woman away from the car show. Could you talk a little bit about “Design for Dreaming,” the best video of all time?

It is the weirdest. There’s a lot of those industrial shorts that were produced in that era, and the woman who stars in it was actually a Broadway star of some renown at the time. She would have been someone who people recognized seeing it.

What you’re seeing there is the convergence of the kitchen industry and the car industry, which to us sounds like a weird pairing, but really was par for the course for that era. Frigidaire was owned by General Motors, and if you went to Motorama to see all the cool new cars, you might also see a cool new kitchen, and those were being presented as being of a piece. These are the new amazing devices, and they’re designed with this cohesive look and feel, and that’s another thing where the colors echo. If you think of each decade as having a mood board, the colors of the cars and the colors of the appliances are closely tethered together.

And the idea that she would be whisked away by this mysterious man is telling, because in terms of purchasing power at the time, and you see this throughout a lot of the advertising, the ads are aimed simultaneously at men and women in different ways. For men, you often see things like the Frigidaire ad that says, “get more wife and less housewife.” Her life will be easier, so she’ll be less bedraggled and able to be glam and pretty. You, the wife, will be dazzled by how amazing all these devices are, and you, over here, the husband, who’s going to be probably buying it, will be dazzled by how glamorous and relaxed your wife is. There’s dual-stream advertising.

And so the film, where she’s whisked away by this mysterious man, I think of that as being like possibly this strange hint that husbands, you better get in the game with the latest appliances, because your wife could be tempted by some mysterious dude who takes her to see these mysterious appliances. That’s probably a bit of an editorial stretch on my part, but definitely it plays into that weird complex gender divide.

I guess it also plays into that narrative of what your whole life is supposed to be in the ’50s—Prince Charming will whisk you away to the suburbs and present you with this pastel pink kitchen.

Right, exactly. They drive off into the sunset at the end, because it’s Motorama.

There’s one image in here that I particularly loved where it’s this pink kitchen that’s carousal themed, to the degree that there’s literally a carousel horse in the kitchen. How far did people in practice take these designs? Would anybody have actually done that?

If anybody actually had anything like that, it probably would have been a Hollywood celebrity. That kitchen comes from the Formica World’s Fair house, which was part of the 1964 World’s Fair. It was showing you how Formica could be used in all walks of life, so it was all over the house in all different rooms. But of course it does lend itself really perfectly to the kitchen, even now. That was meant to be using Formica to create patterns in this really fun way, and there’s all these different colors. Any color that you can think of—you can create this magical soda shop carousel fantasy, if you want!

It’s funny that you bring it up, because I’ve noticed that that image really speaks to people now. Strangers on Instagram will tag that and be like, “Oh my God, I want this, I want to live here.” They captured something that transcended their own time period when they designed that. I think in terms of “real life,” in terms of what actual people would have had, you probably would have looked at that and said, Okay, maybe I’ll do pink and red dishtowels, or maybe pink and red Formica, but not quite that over-the-top. It’s sad to me that that’s fallen out of favor a little bit, because people’s kitchens are so monochromatic and have a tendency to be so austere, that people probably have a little bit of a longing for color, and that’s probably why people love that image.

I have to say, I know that avocado is a tough sell at this point, but sometimes you’ll see a Trulia listing of a house that hasn’t been renovated—I’m so tired of the white, the subway tile, that it’s starting to look a little cold instead of clean, and I love these things that are so bonkers.

Oh yeah, and it’s a form of unusual color and experimentation that doesn’t tend to happen other places in the house. There was this notion that the kitchen is literally where you make stuff, and in some sense it can also be where you experiment with design. It can be the test kitchen both for food and how it looks.

I love that, too, that you see the outer space vibes. We talked about this when we talked about midcentury Christmas—like you see space creeping into Christmas, you see space creeping into the kitchen.

Right, which is even weirder in certain ways. There’s a whole Pyrex pattern that’s inspired by the moonrise. You’re sitting here in the kitchen reading about exploring space—but don’t leave the kitchen! That’s where you belong! It’s such a funny juxtaposition. I’m trying to imagine a company advertising that way now. You’d have the perfect space-faring coffeemaker or something. You really don’t see a lot of that these days. There was this moment when the Space Race, around the time of the moon landing, was really inspiring to people, and everybody wanted to get in on that. We would think of it now as web traffic. Oh, it’s trending, we have to get in on the Space Race.

My other favorite version of this, the “future but stay exactly where you are” juxtaposition, is in the imagery for the Frigidaire “Kitchen of Tomorrow.” It kind of looks like 2001: A Space Odyssey, like she’s running the NASA command center or she’s on Star Trek, but she also looks like she’s doing secretarial work.

Exactly! At the little desk. Also, toward the end there’s the Honeywell kitchen computer, which is basically a giant calculator, because computing in that era, that size, that’s the best it does. That’s what its capacity would have been. You could maybe have done calculations and stored a few recipes, but it’s not going to be life-changing the way a dishwasher is life-changing. But there’s this sense of, that is a way people become used to seeing women. If you are in the workforce, you are dressed the way the woman in the model kitchen is, Anne Anderson, in the shirtwaist dress and these really attractive little high heels, sitting at a desk with a pencil and ready to take dictation. Because she’s a professional, right? She’s presenting this kitchen in a World’s Fair context, so she’s at work. She’s not at home. She’s doing this funny kind of work where it’s domestic, but it’s really in a professional context.

The way that she’s dressed and the fact she looks so polished—that is part of what you’re buying. You’re buying machines, ideally, but you’re also buying this vision of yourself where you don’t have to be grimy and sweaty and working really hard physically. You can be really polished and put together and look like you’re ready to go out to lunch.