Image: Angelica Alzona/GO Media

In July 1959, a young and disconcertingly handsome Vice President Richard Nixon turned up in Moscow in a fashionably skinny tie for the grand opening of the American National Exhibition. The exhibition was hosted by the American Embassy in Moscow and lavishly spent American tax dollars in the hope of narrowing the gap between people in East and West. Its real aim, to demonstrate the advantages of capitalism on Soviet soil, bobbed right beneath the surface. The exhibits featured all of the trappings of Baby Boom-era America: color television sets, cars, boats, sports equipment, home appliances, a children’s playground, and even a full-scale model home affectionately nicknamed Splitnik, which was cut in half and swung open like a dollhouse to let Soviet visitors see how the “average” American family lived.

On opening day, Nixon led Nikita Kruschev into the kitchen on Splitnik’s first floor, and pointed to the built-in dishwasher installed beneath the counter. Such things, Nixon explained, were mass-produced in the United States in the interest of making women’s lives easier. Kruschev scoffed. The Soviet Union had “such things,” he told Nixon. And anyway, Soviets did not share “the capitalist attitude toward women”: that their highest contribution to society was being full-time mothers and housewives. Soviet women were workers, busy building an industrial society. Nixon retorted, “I think that attitude toward women is universal. What we want to do is to make more easy the life of our housewives.”

The American press covered the “Kitchen Debate,” with no small amount of glee, painting Soviet women as hassled and unkempt, bound to jobs that robbed them of their looks and led them to neglect their husbands and children. The American housewife stood in luminous contrast; her ample home appliance-provided leisure time kept her sexually attractive and available to her husband, attentive to her immaculately clean and tastefully decorated home, and devoted to the demands of raising middle-class children. At the height of the Cold War, how and where women spent their time, working or childrearing, cut to the very core of national identity and economic ideology.

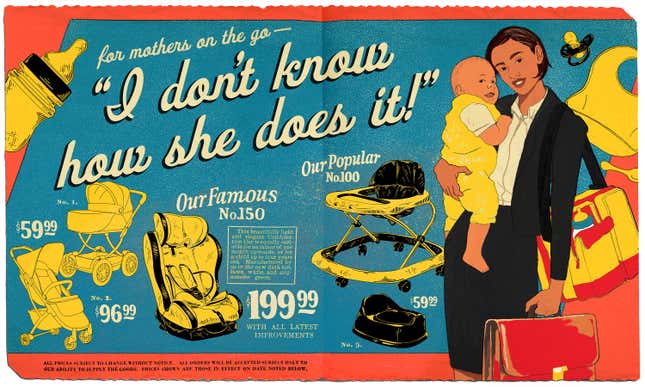

That consumerism and motherhood remain close bedfellows will hardly come as a surprise to anyone who has driven by a Buy Buy Baby, the aptly-named emporium of procreation-related supplies, and still less to women of childbearing age who spend any time on the internet. In my early 30s, the advertisements for engagement rings and wedding dresses that had followed me around the internet for much of my 20s disappeared, and a barrage of pregnancy and motherhood products rushed in to fill the void: maternity workout clothes, maternity capsule wardrobes, maternity yoga classes, stretch mark cream, diaper cream, diaper delivery services, a Keurig-like device that produces appropriately-heated bottles of formula, nursing lingerie, cordless breast pumps designed to be worn, very specifically, under a suit and on a train, and heated, vibrating breast massagers that must have some reproduction-related function, though I couldn’t tell you what it is.

I buy plenty of things on the internet, none of them breastmilk-related. But if the parade of nursing bras in my feed is any indication, the algorithms that drive today’s digital economy are specifically interested in one kind of consumption for someone my age and gender: the kind associated with motherhood. “No wonder it’s unpopular to not have babies,” a friend observed wryly when I showed her an ad for a $99 product called Tushy, which claims to enhance the postpartum pooping experience. “It’s bad for the economy.”

The connection between reproduction and the economy has not escaped the notice of today’s policymakers. In 2017, then-Republican Congressman Paul Ryan declared a “new economic challenge for America”: to have more babies. In March 2019, Senator Mike Lee, a Utah Republican, stood in the Senate to offer “the solution to so many of our problems, at all times and in all places: fall in love, get married and have some kids.” Lee’s point was that procreative sex would somehow save us from the coming climate catastrophe, but the root anxiety is the same. As the American birthrate dips to the lowest point in its history, conservative politicians have started panicking about America’s future economic stability.

Ryan and Lee are on to one thing, historically speaking, even if they don’t seem to get that correlation and causation aren’t the same thing: birth rate and economy have surged together in the past. As World War II ended, federal and corporate policies, as well as social norms, encouraged the six million American women who joined the workforce in the wartime years to leave their jobs to the soldiers returning from overseas, get married, and start producing America’s next generation. Inspired by the prevailing traditionalist propaganda or by government programs that made suburban homeownership extremely attainable for the families of white veterans; women answered the call. The resulting Baby Boom reversed a two century-long downward trend in the American birth rate, and between 1946-1964 women in the United States delivered unprecedented numbers of babies, 72.5 million in total.

The rapidly increasing number of mothers, and the attendant desire to “make more easy” their lives did play a role in driving the American postwar economy, though not nearly as large as the buildup of our nuclear arsenal. Advertisements for appliances, laundry detergents, home goods, and convenience foods filled the pages of women’s magazines, alongside ads for pills to help women manage the workload. “Why is this woman tired?” asked a 1956 ad for the pharmaceutical giant Smith Klein and French, as an exhausted-looking woman leaned back on a sink full of dishes. The solution was the amphetamine Dexedrine, which promised “energy.”

By staying out of the labor force and acting instead as a consumer, buying things for the good capitalist children she devoted herself to raising, the American housewife and mother was essential to capitalism’s Cold War triumph

The media, politicians, and captains of industry regularly reminded Americans that women’s much-touted leisure time—the demand for amphetamines notwithstanding—was a gift of the capitalist system, purchased through men’s participation in the economy and women’s consumption of its fruits. By staying out of the labor force and acting instead as a consumer, buying things for the good capitalist children she devoted herself to raising, the American housewife and mother was essential to capitalism’s Cold War triumph. Facilitating her continued existence, through political encouragement or by creating consumer goods to help her out, was, therefore, a matter of national importance. It is the ghost of the Baby Boom-era mother that Paul Ryan, Mike Lee, and others want to revive.

But they are not the first to hold a seance for her. In 1971, as the Baby Boom tapered off and women’s liberation movements gathered steam, the United States Senate passed the Comprehensive Child Development Act. The Act would have established a system of federally-funded childcare centers that charged on a sliding scale for daycare, after school care, and pediatric medical and dental services. But when the bill landed on the desk of then-President Nixon the following year, he vetoed away the dreams of working mothers. Daycare centers were downright un-American, maybe even communist, Nixon explained. He may have wanted to make life easier for housewives, but he did not want to ease the lives of women who did not want to be housewives, or who, due to their marital status, racial background, or economic circumstance, did not have the choice to forgo paid employment. Conservatives of the time believed that the strength of the traditional family unit was America’s strength. Feminist demands for equality threatened the institution of the family, as well as national security and global superiority.

This particular American importance placed on motherhood as women’s primary civic contribution dates back to the late 18th century, during and after the Revolutionary War. The wives and daughters of patriots were transformed into “republican mothers,” who served the infant nation by birthing and raising its next generation of citizens, bathing their progeny in American civic virtue and spoon-feeding them American morals. Dependent on her husband but in command of her home, chaste but wise, the republican mother was a cultural icon of the post-revolutionary period. She also served a practical purpose. Infant mortality rates had fallen by the late 18th century, meaning fewer births were needed to produce a desirable family size. With less time spent pregnant or recovering from childbirth, white, middle-class women had more time on their hands. The patriarchal society in the budding republic was very happy to direct women’s time toward motherhood, by building it up as their most noble calling. The Baby Boom-era mother was herself a ghost, a revival of the republican mother.

Of course, these idealized visions of motherhood, the ghosts of the past that conservative politicians so dearly want to revive, have real consequences in the present. The ideal of full-time motherhood, whether in the image of the republican mother or the Baby Boom-era mother, has always implied a critique of black, immigrant, impoverished, and working-class women—women who have historically not had the choice to participate in the economy exclusively as consumers. It also casts a societal side-eye at women who chose another path, whether pursuing careers alongside childrearing or forgoing motherhood altogether. Efforts to breathe new life into these mothers of Americas past also resuscitate criticisms of women who do not, or cannot, fit their mold.

If full-time motherhood has historically been the capitalist ideal, then it’s ironic that the products that fill my feeds recognize our modern reality: that most women in the United States have already broken that mold. According to the Department of Labor, 70 percent of American women with children under 18 work outside the home. Delivery services, breast pumps for the train, and professional maternity wardrobes are designed to help the working mother balance what sociologist Arnie Hochschild called the “second shift,” a balance they have long struggled to achieve. As the career woman rose to shoulder-padded prominence in the cultural imagination of the 1980s, some feminists started to catch wind of the scam: society expected women’s expanding professional contributions to come in addition to motherhood, not in place of it. As it had been for non-white and poor or working-class women for generations, motherhood was the working woman’s second full-time job. “No one had to tell me it was harder to have a job and be a mother,” the narrator of Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s 2019 novel Fleishman is in Trouble observes. “It was obvious. It was two full-time occupations. It’s just math. Because having a job made you no less of a mother; you still had to do all of that shit, too.”

Contributing to the economy through her working labor does not get a woman out of her expected role of contributing to the economy as a mother, and as a consumer of the ever-expanding slate of products deemed necessary for successfully raising children. It’s fundamentally about how to extract the most labor from women, whether commodifying motherhood or pushing women to participate as both workers and as mothers. But motherhood, and the money a woman spends on raising her children, is non-negotiable.

Reviving the ghosts of American mother past won’t help the economy because it’s never really been about the economy

Despite this, it’s not clear that reviving the ghosts of American mothers past will actually benefit the economy as much as policies that help women in the workforce, mothers or not. A 2015 McKinsey study found that $28 trillion would be added to global GDP by 2025 if women worked at the same rate as men. The bad news, for Ryan, Lee, and others who think that occupied wombs would portend a stable future, is that the booming postwar economy likely facilitated women having babies as much as the other way around. And the realities of our current economy—that the United States is one of only two countries in the world that do not require paid maternity leave (the other is Papua New Guinea), for example, or that high-paying jobs are increasingly greedy for workers’ time, or the crushing load of student debt Millennials carry, or that teachers are having to drive for Uber in the evenings to make ends meet—explain much about why the birth rate has dropped in the first place.

Reviving the ghosts of American mother past won’t help the economy because it’s never really been about the economy. Concern about what women do with their bodies and their time has always been about ideology. Motherhood has long been offered to women as the most valuable contribution they can make to American society, facts on the ground—or their own ambitions or desires—be damned. And it still is. That’s what the breast pumps in my feed are trying to tell me.

Peggy O’Donnell is a writer, historian, and Lecturer at the University of Chicago. She tweets, occasionally, @peggyohdonnell.