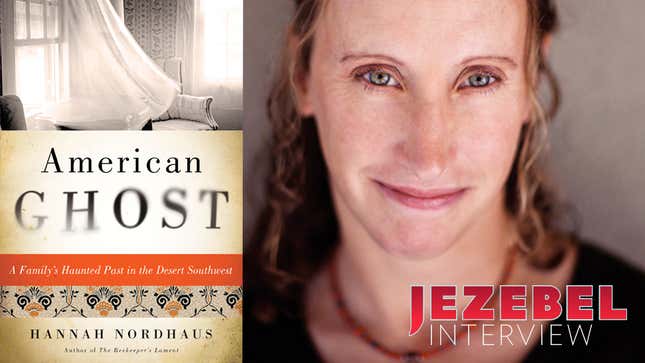

Author Hannah Nordhaus on Chasing Her Ghostly Ancestor Julia Staab

In Depth

There’s a woman said to haunt Santa Fe’s La Posada Inn.

The building was a private home before becoming an inn, built for Julia Staab. Julia was born in Germany, but she married a man from her hometown who’d struck it rich supplying settlers and soldiers in the New Mexico territory. And so she traveled halfway across the world to bear and raise several children far, far from everything she knew. Now she’s a local legend, and all sorts of stories have sprung up to explain why she might’ve stuck around. Most of them are very dark. This segment from (wait for it) Unsolved Mysteries is a pretty typical depiction:

But ghosts have descendants, too, and among Julia’s is author Hannah Nordhaus, who set out to unravel the mystery of who her ancestor really was. This involved research into European spa culture and nineteenth-century women’s healthcare, the spiritualist movement and the growth of Santa Fe. She talked to ghosthunters and psychics and dedicated Julia enthusiasts. And then, once all her research was done, she booked a night at La Posada.I talked to Nordhaus about American Ghost, the book that resulted.

It’s always interesting to me what projects pan out. What pushed you to write about Julie and your family’s history? What tipped you over?

I was trying to think about my next project after my last book, which was about honeybees and the beekeeping crisis that’s been affecting honeybee populations worldwide. Julia wasn’t the first thing that came to mind. My dog died right before my last book came out, so I thought about writing a dog memoir. And that did not pan out! Not every idea does.

Julia Staab is someone I’ve thought about my whole life and known about her. I had written about her before, as I mention in the book when I was a younger woman. At the time, I think I was really writing about myself more than I was writing about Julia. It was about Julia as a young bride coming from Germany to New Mexico with her horrible husband and being kept down by men. I think at that point in my life that’s how I felt I was being kept down. So I wrote that article when I was 24 and just moved on with my life and became a journalist and wrote about science and the environment and stayed away from ghosts. Then, sometime after I realized the dog memoir was not something I wanted to spend two years writing, I remembered I had found this book that my great-aunt Lizzie had written about our family history, and I realized that there was a lot more to my family than just these ghost stories. And I suddenly was at a point in my life where I wanted to learn more and in a place where I had the opportunity to do so, as a writer.

One of the things that fascinated me was how well you were able to flesh out Julia’s family and her world and get so close to her, but at the same time, it was hard to get final, definitive answers to many of the big questions. You still end up wondering about the core of Julia. Did you learn what you wanted to learn?

About Julia, no. But I learned so much more about her family, the people around her. She was so enigmatic and so reclusive and didn’t leave any records, really, so I had to trace her life through the people around her. And I did not get satisfying answers to a lot of the questions that I started with—what exactly was her ailment? Why was she unhappy? I have a lot of speculations based on things I learned, but I can’t tell you right now exactly why she was unhappy, how she died, whether she’s a ghost. I wish her ghost had come to me in the hotel room and said, Let me sit down and tell you about my life! But history doesn’t work that way. And it’s not just ghost stories—especially nineteenth century women, their lives were so undocumented and they were so sequestered.

I do feel a lot closer to Julia’s daughters, especially to my great grandmother Bertha. That was something I had not expected. I had found Bertha’s diary a few months into my research and that really opened up Bertha’s world and in some ways Julia and the family’s world and what they did, who they were. Bertha, by some contrast to her mother, led a really remarkable and productive and, from what I gather, happy life. She’s become a model to me in how to approach the sadness in our lives, the challenges, and she was by all accounts beloved and really engaged in her world and in her community in a way that her mother wasn’t.

But Julia really did remain a cypher.

I loved that though. When you’re writing something like this there’s a certain pressure to overstate your case, but you were really comfortable laying out what we have, what we don’t have, what we can maybe think about. Something like Abraham and whether he really donated to help build the Catholic cathedral and whether they put the Hebrew lettering on over the entrance had anything to do with him.

We’ll never know.

Yeah, here’s where the trail ends.

It’s not how narrative works! I saw you guys had posted that story about Hootie and the Blowfish and Rolling Stone—there’s so much about narrative and the pressure to provide narrative enclosure in journalism. And because my background’s in history and especially women’s history in the nineteenth century, there’s just so few answers. There’s so little definitive—but even, we’re always making leaps, suppositions, especially when it’s about people’s emotional lives, when it’s about what drove them, why they felt the way they did.

So you know, as a historian, and my background is I did study history, you do have to be comfortable with a lot of holes in the stories. But I think people who love ghost stories—I guess people who love ghost stories, too, there’s a lot of holes—so hopefully they won’t be mad at me.

But you can’t wrap it up neatly. I am comfortable with that, but it’s sometimes hard to explain to people.

It was interesting, too, to think about how everybody in that family knew what was going on and in many ways it dominated their lives, but when it comes to write it down in your diary, you write about the guy you had a crush on. You don’t write about your mom’s terrible accident.

And I think now we probably would, because we write about everything and we’re so confessional in our writing. But that was not how they worked back then.

You know, the other thing I would say is I studied a lot of women’s history and there’s a lot of really good examples out there. And it’s mostly academic history, trying to piece together women’s lives that were pretty poorly documented. So I did have those models, which I’m very grateful for. There’s Jonathan Spence, who wrote The Death of Woman Wang, which is about a woman in early modern China, and there’s a book called The Midwife’s Tale, which is about a midwife in colonial Maine. And both of those, they had some records. And there’s another book called Lucrecia’s Dreams, which is about the Spanish Inquisition. So there are these wonderful history books that try to piece together people’s lives from these really sparse records. I think it’s harder to do with popular writing, with more narrative stuff, and so I just had to trust that my readers would go along with me on that.

You had to find your way into Julia’s story through other people’s stories, and one I thought was interesting was Abraham. The ghost stories want to make him out to be this whoring gambling abusive monster. But your findings suggest that it was more complicated. Where did you come down on him? What was your final sense of him when you finished the project?

I think Abraham was not a horrible person. I don’t think he was the villain the ghost stories make him out to be. I am glad he wasn’t my husband.

He was very much a man of his time. I think he was incredibly personable, charming, funny, energetic. I probably would have been very taken with him if I had met him back then in his heyday. That said, he was a nineteenth century husband and a nineteenth century father. I think in many ways, what I encountered was he was a far more horrible father than he was a horrible husband. It seemed to me that he really did care for Julia and try in his own limited capacity to help her and mostly that involved hiring people to help her and sending her off to spas. I don’t think he really quite knew how to deal with her ailments and from Bertha’s diary, it seems he was actually quite loving father to his daughters as well. Strict, I think, but loving. But I think he was really, really tough on his sons, and I think they suffered for it.

So where I came down with Abraham is, I am fond of him. I have a fondness for him. I think he was a man of his time, and it’s hard for us sometimes and especially when we’re speculating in ghost story realms to understand that marriages functioned in different ways back then.

Why do you think it is that Julia ended up being this legendary Santa Fe ghost? Out of all the women who lived and died in Santa Fe in the nineteenth century—and as you point out, someone like her contemporary Flora Speidelberg leaves a much clearer paper trail and would have probably been more widely known or at least more out and about. Why do you think it was her story that ended up having this afterlife?

Well, I think there’s the archetype of—especially in the Victorian ghost story—the sad wraith-like spirit floating around. You know, someone asked me at one of my book signings, ow do you know that Julia was always sad?And I don’t know that. But I thought about it, and, you know, Sister Blandina the nun [who traveled with the family] wrote about Julia being depressed. I didn’t even know they used words like “depressed” back then. But she described her as depressed. And then in Bertha’s diary it just goes on and on about how she’s panicked or she’s having a bad spell, and it’s clear it’s emotional, not just physical, but there’s clearly some physical stuff too.

But never once did anybody say “Julia’s happy today.” So I do think that whatever in the public memory remained of her story, people did know that she’d lost a child and she was clearly not a happy public person. So perhaps that legacy passed on.

And then, people said they saw a ghost in her house. So who else would it be? The first thing that ever mentioned (I saw) a ghost in the house, someone thought it was a servant named Ida, but pretty quickly that turned to it was Julia. And it made sense—she was the mistress of the house that was built for her.

I hope poor Ida isn’t haunting that hotel thinking, This is incredibly rude of everyone.

Yeah, there’s a paper trail that I’ll never find.

You know, I didn’t write about it in the book, but at my family’s place in northeastern New Mexico, where I found Lizzie’s book, that was Bertha’s husband’s property. There’s supposed to be a ghost there, and there’s a lot debate over whether it was Bertha or one of the nannies who took care of the kids. There’s a picture there and people keep saying, “Oh I saw that ghost and it’s Bertha.” But the picture’s actually of the nanny. So there’s probably a lot of misidentified ghosts out there.

Do you think it means something that this sad Victorian ghost woman pops up so often? Do you think it means something that we keep reanimating these women, building up a mythos and writing articles and telling stories and staying in hotels? Why do you think it captivates us?

I think there’s a couple things. One of the reasons I went into the spiritualism stuff, about the Fox sisters, is this Victorian archetype of a ghost really arose out of the Victorian era and how obsessed people were with ghosts back then. A whole huge religious movement grew out of the notion that we can communicate with the dead. And all these seances and Vaudeville spiritualism acts all happened during this period when they were dressed in Victorian clothing and most of the mediums, the real famous ones, the majority were women. And it was a way for women to be public figures when they weren’t allowed to be in any other realm and be out in the world.

And so I think that the Victorian ghost story really grew out of that cultural movement. And that’s just what we think about when we think about mediums and ghosts and seances—women in Victorian dresses. You rarely see a ghost in, like, a mini-skirt and platform shoes. It’s always in this high-necked dress with her hair pulled up. I do think there’s definitely a cultural archetype. And again, because women were so sequestered in that era—there’s a lot of scholarship around the domestic sphere. Women were supposed to stay in the home and were not supposed to be public figures in any way. Flora Speidelberg and Bertha were much more modern women than Julia was. So you have this image of women like Julia, who were just locked up in their homes and died there and never left.

It’s almost like looking at ghosts of ghosts.

Yeah, and ghosts of a movement in the American imagination.

So, I get the sense you’re a skeptic. Did it change your feelings on ghosts to write this whole book about Julia, a legendary ghost?

It did and it didn’t. I am still a skeptic just because I’m an empirical person and it’s really hard to get empirical about ghosts. People try, but hey never succeed. That said, I want very much to believe. I love the story, I love the power of the story. I love how these ghost stories connect us to the past and if nobody believed they were true, they’d have a lot less power. And in writing this book and promoting it now, I have heard so many ghost stories from otherwise “normal” people who are generally skeptical, believe in science, are not woo-woo in any way. I’ve heard probably fifty stories since this book has come out, where people explain something happened to them that they can’t explain. They never believed in ghosts before and nothing’s ever happened again—just this one time. Who am I to say you’re full of shit? They believe it happened to them; they seem like perfectly sane people. So I’m not going to say I don’t believe. I remain on the fence but with a strong predilection towards wanting to believe.

You cover so many areas in your book. Is there anything in particular that you came across that really interested or surprised you?

I thought the women’s health stuff was really interesting—how they basically treated emotional and gynecological ailments as the same thing. I knew there was some measure of that, but I didn’t quite realize that they were giving women hysterectomies for depression. And just exploring the sort of barbarity of the medical treatments that women were subjected to was really quite astonishing.

The other really surprising thing to me was that Julia had had a sister who’d lived long enough to be killed in Holocaust. Because I had no idea. I knew that my family was German and there were probably people who had not survived the Holocaust. But I had no idea that it was quite so close to home.

You start the book reading about how Julia left this beautiful place where all her family was, and she had to travel to the very difficult to reach ass-end of nowhere (at the time) but it saved her life. Or, it did and it didn’t I guess.

It saved her children’s lives and made it possible for us to be here. But I’m not sure it saved her life. Her life was short and not terribly happy, but it certainly put our family on a much more sustainable trajectory.

Image by Tara Jacoby, photo by Casie Zalud.

Contact the author at [email protected].