A Journey Through the Queer History of Brooklyn, Full of Vaudeville and Poetry

In Depth

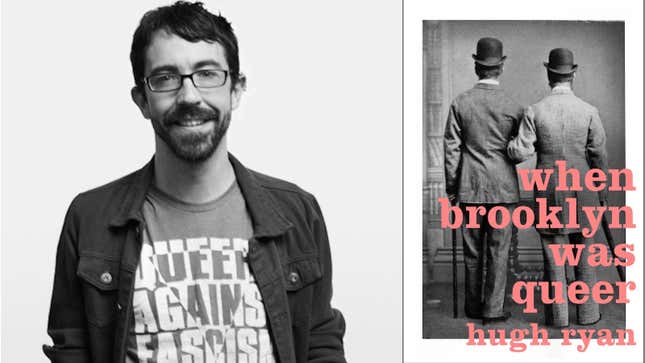

So much of the stereotypical view of mid to late 19th century Brooklyn and America more generally could be summed up by the cover of David McCullough’s The Great Bridge: serious, and very safe as a gift for straight, middle-aged white dads. Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer is a stone thrown into the middle of that longstanding stereotype.

Rather than attempting an encyclopedic accounting of the borough, the book focuses on the world of the Brooklyn waterfront from the 1850s to the 1960s, looking for the conceptual spaces where queer people might have gathered, as Ryan explained. The book is worth reading for the chapter on vaudeville alone, tracing the lives of performers like “male impersonator” Ella Wesner, a huge popular success (paid to promote Little Beauties Cigarettes, like some 19th century social media influencer), who would take up with an actress named Josie Mansfield, who herself had achieved newspaper fame when one of her rich lovers shot another.

Even more fascinating—and tantalizing, considering how much of these live performances was lost to history—is the life of Florence Hines, who performed as a drag king in an African American revue called The Creole Show, based out of Coney Island and incredibly important as it broke with the tropes of minstrelsy, an overwhelmingly dominant form of entertainment at the time.

When Brooklyn Was Queer pairs particularly well with Saidiya Hartman’s recent, incredible Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments—excerpted at Jezebel here—which follows some of the same people and territory. Both books contribute to a deeper, richer understanding of New York City’s history, and an expanded sense of who participated in American history more broadly. (Interested locals can also check out an accompanying exhibit at the Brooklyn Historical Society, “On the (Queer) Waterfront,” which runs through August.)

I spoke with Ryan about how he came to write the book, gender in 19th-century vaudeville, Coney Island, and omnipresent 20th century New York City villain Robert Moses. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

JEZEBEL: For people who haven’t cracked open the book yet, the title is When Brooklyn Was Queer. So: when was it? What’s the period you’re focusing on?

Hugh Ryan: The period the book focuses on is about 111 years of Brooklyn’s history—1855, the publication of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, which he publishes in Brooklyn Heights, all the way up to the closing of the Navy Yard in 1966. That’s really the lifespan of the waterfront in Brooklyn. That’s when it was this economic engine that drove the growth of the city and the growth of this initial queer community.

One of the things I always try to emphasize when I talk about the book is that I use the past tense, even though I know Brooklyn is super queer now and in fact more queer maybe than it’s ever been, but that there was this specific period of time, particularly the 1920s, 1930s, when people would think of Brooklyn as a place to go to for a particularly queer experience. That’s the high point of the community that I’m discussing, and then it sort of falls apart after that. I was born and raised in that period where you would never think of Brooklyn as a place you would go to at all, first off, but particularly a place you’d go to for a queer experience.

How did you get onto the trail of the project?

It was pretty funny, actually. I had started this museum called the Pop-Up Museum of Queer History, and we were a collective that did community-sourced art exhibitions about queer history in queer spaces, to ask this question, what would a queer museum look like? It was after the Hide/Seek show had kicked the Wojnarowicz exhibit out of the National Portrait Gallery because it was sort of too queer, and I was really interested in exploring this idea of what would our history look like if we controlled it, and we controlled the spaces it was presented in?

The first one I ever did was in my apartment in Brooklyn, and 300 people showed up. It was way too big, we got shut down by the cops, and I was shocked! I thought I was throwing a one-night party that would be kind of fun and cute, you know? But all of these people came, and I realized we’d hit on something that really mattered. So after a couple of shows, the collective thought, well, we should do one about Brooklyn’s history! That’s where we started. That’s where many of us lived. Then suddenly we realized that we knew nothing about the queer history of Brooklyn. And usually when we put out these calls—we did one in Philly before that, saying we really want to focus on local queer history, and people had lots of things to suggest. But when it came to Brooklyn, people didn’t know anything.

So I thought, well, I’ll go to the library, and I’ll get out the book. Because I was convinced there would be a book. And it would have probably been published in the early 1980s, by some small gay press that had gone under, had been completely forgotten, hadn’t been checked out in 15 years—but I was certain something would exist. But then it didn’t! I looked for websites and documentaries, and there really wasn’t anything that looked at the intersection of Brooklyn and queer history.

I was already a journalist and a curator, and I was talking to a lot of people about queer history regularly, so I just started to collect little bits of information to answer the question for myself. Brooklyn and Manhattan have always had this intimate relationship, and maybe there were some reasons why queer people mostly gathered or organized or made their lives visible on the other side of the East River. That was the initial question for myself, to find out, is there history enough here to do something with? And the answer was overwhelmingly yes. But it really was because I was so ignorant that I came to the question to begin with.

Had this history been actively hidden, or was it that people just didn’t think to look?

I think it’s a little bit of both. There are definitely parts that are actively being destroyed, even as it’s being built. Pretty much everyone that I look at in the book, at some point you get to the point in their biography where it’s like, “and then she burned her diaries.” Or, “and then his mother destroyed his letters.” That was definitely happening, even at the time. Then you have compounded upon that—I mean, I don’t know about you, but I learned about Walt Whitman in high school, but I didn’t learn he was gay. Even though he’s one of the few figures in my book where I think you can very reasonably say that most people knew that he was gay many years ago. And yet that gets hidden. It doesn’t get talked about. It gets suppressed.

Then there’s a level at which I think it’s not particularly about queer history being suppressed or destroyed or forgotten, but the history of people who are poor, and the communities of people who are poor being destroyed. So Robert Moses does all of these things that he does when he’s building highways. He destroys them because they’re poor communities, and they can’t really fight back. And inside those are a lot of really queer communities. He destroys Coney Island, and Coney Island provided space for queer people. He wasn’t aiming at queer people, but he certainly destroyed the history of queer people as part of what he was doing, because poor people are queer and he didn’t care that much about poor people.

Then, of course, I think there’s just a certain amount of it that just gets forgotten. For a very long time, Brooklyn was positioned as a place that people came from, but not a place that people went to. It was the bridge and tunnel, and you just didn’t look at it that closely, and it wasn’t important.

There’s a level at which I think it’s not particularly about queer history being suppressed or destroyed or forgotten, but the history of people who are poor, and the communities of people who are poor being destroyed.

That’s how all of those forces combined, and then you have the real homophobia that takes root in American post World War II, that tells you that homosexuality is dirty and disgusting and small and needs to be policed at all times and we need to look out for it in our lives and condemn it and report it and look for it in ourselves and condemn it and destroy it. That homophobia that takes over in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, I think really helped to cement this idea that there was no history before that, and if there was anything, it was small and sort of terrible.

When I got to the part with Robert Moses I was like—oh, of course. Robert Moses strikes again!

I know! It’s really amazing, he fucked everything up. I often wonder, if he had loved public transportation instead of cars, what city would we be living in today?

You go into a lot of detail about late 19th-century theatrical culture in Brooklyn, and you talk a lot about this working-class universe of entertainment, and how there’s just so much happening there. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about that part of the book?

I mean, it was fascinating for me to discover that. That was something I definitely stumbled into in doing this. I knew that there were some performers who were queer. And I started to read about drag kings or drag queens. I mean, they wouldn’t use that term, they would have been “male and female impersonators.” But the roles were the same. I started to think about it, because one of my questions in the book was not just what people thought queerness was and where queer people were, but how we heard about it. How that information was spread. And I began to realize that in the late 19th century, it really was theaters. There was a place in the vaudeville culture for masculine women and feminine men. Much like those stereotypes about the drunken Irish Paddy were spread by vaudeville, you have the “fairy,” the effeminate man, that story gets spread too.

That for me became really important, because when you have those performances that originate in New York City, in Brooklyn, and then travel the country—New York City was definitely the epicenter of vaudeville—you’re bringing culture from this place of rich cultural mixing all throughout the country to create that national tapestry. Then you have this boom in newspapers that are reporting on both those actors and the shows, and so it’s then amplified—even the people who can’t get to the shows are going to read about them and know about them. And so what those people were doing had an outsized effect on the rest of society.

Then when I looked really closely, I realized that not only were these people playing with gender in their performances, but many of them were queer. And even the ones who weren’t playing with gender were also queer, and they were using that life, that ability to move around the world, to—if you were a woman particularly—have economic freedom and privilege to build an independent life. The ability to move in and of itself was important, because that meant there weren’t too many people watching at all times. You were always one step ahead of the moralists. And you were expected to be a little weird, a little out there. Maybe you didn’t get married, you didn’t have children. These were things that were acceptable among artists, because they were a little eccentric.

That provided this space. And once I understood that conceptual space—a lot of the process of this research was understanding where there was conceptual space for queer people, and then actually going into the records and saying, what do I find? If I believe that there is a space for queer people in the theater for all these reasons, what records could I find relating that to Brooklyn? Often there were very rich records. That’s how I did my research. That’s why I think the theaters were so important. They also offered space for people of color. It was not the same amount of space; it didn’t pay as well; it was not as prestigious. But it was a place to find the stories of queer people of color that were kept almost nowhere else.

I think that’s what’s interesting—you’ll encounter stories of individual performers that makes them seem exceptional, but when you get beyond the Great Man theory of history or whatever, and you start looking for people—once you make an effort to look for, like you said, that conceptual space, people will start popping up in much greater numbers than the narrative teaches us to expect.

Yeah, absolutely. I think because so much gets forgotten so quickly, only certain exemplars stay with us. I think of today—there are a million writers that I want to read, but who’s going to be remembered in fifty years? That doesn’t mean the rest of those writers don’t exist and didn’t have a significant impact on the culture at this moment, but we may only remember three or four of them in 50 years.

It’s interesting too because I feel like with vaudeville, people think of there being much less travel of information in the 19th century. Just because vaudeville isn’t a big feature of our lives anymore, people forget that there was this big national distribution network—every half-way decent town in America had vaudeville.

Yeah, and I think we forget that books got maintained, but those early plays, those shows, the things that vaudeville performers were doing, they didn’t get written down or recorded in a certain way. So we can’t point to specifics very easily and say, ah, that one maintained its place in culture and helps define queer people going forward. It’s all gotten lost. We just have indicators of this art form.

Particularly when you get to queer people of color, those performers, very little got remembered of what they said and did, even when it was incredibly important, like Florence Hines and The Creole Show. And I think that that’s a shame, but it also means we have to revive it as much as we can. We may not be able ever to find all of those performances, we may not find those scripts, but you see enough listings of the female impersonators playing fairies in variety shows, even if you don’t know what the show was, you start to realize “the fairy” was a conceptual space—not the same thing as being a trans person or a gay man today, but it overlaps. It was a place where we could talk about queerness, even if that’s not exactly what they were saying or talking about.

To some extent, the queerness of Brooklyn was visible to outsiders in various ways. What did the outside world make of that? From what you can see in the record, when people are encountering these shows, what are they making of that, and how does it shift over time?

The earliest stuff, you get people trying to decide what it means, or what’s important, or what is right and what is wrong, what is good and what is bad. You get constant arguments—you get some people saying, well, any display of queerness is wrong! And you get other people saying, eh, it’s unusual but not evil. There was a lot of conflict and debate and also discussion about what is sexuality? Because in the Victorian era, sexuality wasn’t really a thing—it was about your gender. Who you were attracted to was one part of your bigger ability to conform to what you were supposed to be as a gendered person, not a separate thing that we think of it as today.

But that changes over time, particularly once eugenics comes in, and psychology. Those two forces combine in the early part of the 20th century and start to definite queer people as always wrong and bad, and you get much more negative takes after World War II. You get this increased visibility of queer life in the teens and the 1920s, that then gets a backlash in the 1930s. In the 1940s, you have the war, which shifts everything around for a moment. The growing homophobia in America hits pause; the army throws all of these men together and all of these women together in space where there are not people of the quote-unquote opposite sex, and in civilian life you see the same thing happening. There’s all this exposure to the idea of homosexuality or the experiences of queerness, so that’s this really interesting moment.

But then immediately when the war ends, everything returns to the homophobia that was building in the ’30s. You get this idea that there is such a thing as homosexuality and heterosexuality, that they are different, and they are not directly connected to gender so you can’t see it right off the bat. You can’t tell that someone is a homosexual or is wrong on the inside from just looking at them. And you also can’t you yourself are, necessarily. So you have to start being taught, what does a gay person look like? How do we find these signs? How do we suppress these signs? How do we keep them separate? Because any amount of queerness now might reflect on you, because it’s not anymore about your gender identity—it’s about this hidden thing called “sexuality.” And because it’s invisible, it becomes the perfect scapegoat—like calling someone a communist was really great, because how were they going to prove they weren’t a communist, you could call them gay. You see that over and over again, in all of these crimes, where psychologists who don’t know anything about the cases they’re looking at will say things like “this is evidence of latent homosexuality.” It’s a great thing to say because it makes it sound like you know a lot more than the layperson does, and there’s no way to prove it.

That’s the big change, post ’45, that’s where we get this idea that then becomes this ahistoric idea of what homosexuality has always been. We get this idea that homosexuality is dirty and disgusting and small and needs to be repressed and it’s something to be looked down upon. And then everything that came before it, by making people not talk about it, then it seems like this ahistoric concept that has always existed. There’s always been homosexuality and it’s always been bad.

It probably broke the chain of historic transmission, right? If you found something interesting in your grandfather’s letters in 1952, you definitely burned them.

Yeah! You had to destroy it. It was dangerous.

And then people take the erasure as evidence of absence.

Mmhmm. The erasure becomes the truth. There wasn’t anything to begin with. It’s like the hole that devours itself. We erase what was there, and then we erase the erasure, so it just seems natural.

Here’s a question: who was your favorite character that you encountered while researching this? I was fascinated by the existence of Josie Mansfield, the actress who had one lover kill another then took up with Ella Wesner. She sounded like a trip. Who was your favorite source?

You know, it’s a hard question. But I think that for very specific reasons, Mabel Hampton is probably my favorite. One, her life is amazing. She’s a queer woman who is out at the age of, like, 17 on Coney Island, dancing in the sideshow. She’s there during the Harlem Renaissance, she’s there during World War II, she has this incredible life. She helped to found the Lesbian Herstory Archives. There’s just this epic sweep to her life that we don’t expect, and there are so few other records from some of the things that she’s involved in that we just don’t hear about them in other places. So it’s surprising and exciting to get this first-hand account of what it was like to go to one of A’Lelia Walker’s famed parties at the Dark Tower in Harlem. That’s so exciting.

The erasure becomes the truth.

We have really great access to records from her point of view. For a lot of the other people I write about, it’s things written about them and very little from their point of view. But Mabel has this oral history, so I’ve listened to hours upon hours of Mabel talking, having that level of not only comfort when she’s talking to people who are queer, who know to ask the right questions, who she feels comfortable around, but also just hearing her voice and the way she phrased things and all of that made her seem so human and knowable and familiar to me that she, more than anyone else in the book, feels like someone I know. And that’s a really important moment in queer history! When there’s an older queer generation for queer people to learn from, and then a younger queer generation for people to preserve their records. Mabel’s indicative of that moment.

I mean it sounds incredible to be able to reach through and touch that because she was talking in the ’70s—then you can reach back and touch the ’20s.

And then when you listen to her thing, she says it’s an older woman that first teaches her the world “lesbian,” on Coney Island, an older black woman who says she’s married, but she’s a lesbian. Maybe she was in her late 30s, so she was born probably in the 1880s. What was her life like? She knew the word “lesbian” in 1920, and the word hadn’t been around for that long, so she’s a fascinating figure to think about. And she was there from out west and came to where the performers were and people in the performance troupe. So is she one of those performers from vaudeville? Are we looking at this link that connects us back to people like Florence Hines? I don’t know. It’s unknowable. But you do see those connections growing, and what we would call queer community assembling itself.

Reading this really transformed my understanding of Coney Island. The packaging of nostalgia content about Coney Island—I think it privileges girls who look like Esther Williams in bathing suits, and it implicitly privileges this very “When Coney Island was nice! And we had attractions!” kind of narrative. And the book made me feel like Coney Island has always been this very interesting place that you don’t necessarily see it being presented as interesting in the way it really was, if that makes sense.

Yeah, absolutely. I grew up seeing Coney Island as tawdry, almost, and that tawdriness as being a negative, and not understanding it as this place that broke all the rules and was exciting for that reason. People flocked to it because it was a place where conventional morality broke down a little bit. Those spaces where all of these people mixed and the rules broke down at the same time were critical to queer life. I just didn’t expect that at all. I grew up thinking that Coney Island was a bunch of rinky-dink rides on the seaside and graffiti relating to The Warriors. That was about it.

What a discovery! It’s interesting how many different layers of history you get in New York City in a single place. It’s amazing what you can actually find in the same geographic territory.

Yeah, and how those things can be connected. That’s what I loved about doing the research for this book, and why I didn’t just do a history of all of Brooklyn, because that would be interesting, too. But I found a specific arc that said these kinds of queer lives in these places were made possible by the waterfront economy and by the urbanization that the industrialization of Brooklyn caused. It’s not every queer story, obviously, in that time. And there are other arcs to queer community—particularly post the end of this arc, you start to see many arcs starting in Brooklyn. We don’t know exactly where they’re gonna go.

But I was able to see this very specific story start, explode into visibility, and then die off a little bit. And that was sad, but also exciting. It made things make sense for me. That’s what I wanted so much when I started this research into Brooklyn, not just to catalog a bunch of random homosexuals who happened to be in Brooklyn at some point in their lives, but to say to myself, how did the world I live in, how did the identities that I inhabit develop? How did people come to know them, and how did people come to know themselves? And Brooklyn was able to provide that for me, because if you chart the history of Brooklyn becoming a city, it tracks with the history of our ideas of sexuality today becoming popular. It becomes important in the mid-1800s right as the Victorian era is at its height, and then as Victorianism starts to break down it grows, and you see it all the way up through the Depression. You can mirror one against the other, and that was exciting.