Why Rape Was Impossible: A Look at the Terrifying Medical Logic of 18th Century Law

In Depth

Women lied. That was a fact, and it didn’t need examination.

In the 18th century, for any number of reasons, a woman could be called before judge and jury and compelled to defend her virtue. She would be expected to lie; the laws would have been written accordingly. Her body was a mystery, and it was assumed she’d exploit it—lying about her virginity, about being pregnant, about how far along she was, about whether her child was naturally stillborn or harmed by her own hand. The most preposterous lie she could tell, of course, would be that she was raped.

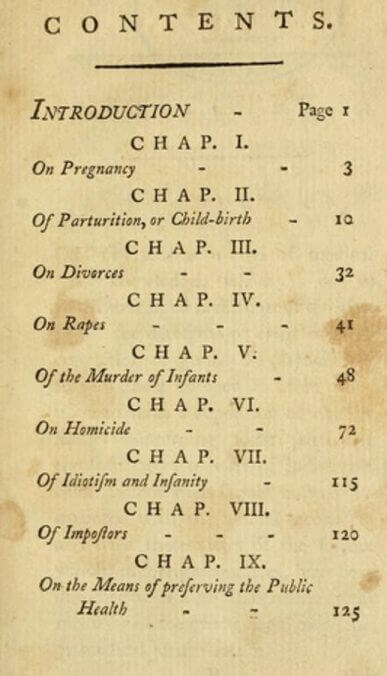

We know about these laws because of Samuel Farr, an English physician in the 1780s. He read a book by foreign “learned professor” Johann Friedrich Faselius, which detailed the medical knowledge most likely to be needed when decoding criminal cases. But Faselius’s book was long, written in Latin, and contained information not applicable to English law at the time (such as the chapter on effective torture). So Farr abridged and translated it for English readers. The resulting book, Elements of Medical Jurisprudence, was meant to help doctors who were called to give testimony in criminal court.

It was a brilliant step forward in the study of forensics. Compiling all that medical knowledge in one place was an advancement in both law and medicine. The only problem lay within the term “medical knowledge.” Science, at the time, was demonstrably improving. It was moving well beyond drilling holes in the heads of epileptics to let the demons out, at least. But it wasn’t yet concerned with stuff like replicable experimentation, peer reviews, or…much anything beyond the “make a guess” step of the Scientific Method. Elements of Medical-Suspicions-We-Have-a- Darned-Good-Feeling-About Jurisprudence would have been a more accurate title.

Nevertheless, Elements is full of intelligent forensic observation on everything from murder to insanity. But mostly, it’s about how damn sneaky women are. This wasn’t a random misogynistic pamphlet or a singular rant. It was a book that courts and doctors grew to rely upon as a guide to decide the fate of women. The information it dispensed would still be used in courts for decades to follow. It helped cement crippling attitudes toward women that reverberate even today.

The Crime of Hiding Pregnancy

To be unmarried and pregnant in this era was a near guarantee that a woman’s life was ruined. And not in the 16 and Pregnant way—in the “die frozen and diseased, huddled against a urine-soaked wall in the London slums” way.

If the father of the child didn’t volunteer to marry her, no one would. She could try and force him to support the child if she could prove it was his, but that was an expensive legal process, and her only evidence would likely be local gossips willing to insist the baby had the accused father’s chin. There was a method by which it was believed a woman would say the true father’s name if interrogated by her midwife or other high standing woman of the community during the height of her labor pain, commonly called travail—but it was not often practiced, possibly because it was silly. Labor is bad, but it’s not torture. A woman can still scream “Richard Simmons is the father!” if that’s what she’s set her mind to. This 16th century midwives pledge shows that a midwife swore not to believe the woman if she accused the wrong man during her labor, anyway, which makes the exercise rather pointless.

No one would employ her either, not just because of her extra burden but because her abandoned character had been revealed. Even her parents likely wouldn’t want her bringing two more mouths back to their table to feed, as in fact, at that stage in life, it was her job to help provide for them.

Consequently, unmarried women were terrified of pregnancy. Even married women could be distraught by the looming of a child they couldn’t afford to bring into the world.

The methods by which women would end their pregnancies will give you an idea of their desperation. They would undertake to have incredibly dangerous, illegal abortions (usually through violent purgatives, or by internally puncturing their own bodies—methods that were often just as fatal to themselves as their fetus). Some would have the baby with the intention of disposing of it immediately. If they were caught, they could claim they’d had a stillbirth. That’s why it was illegal to conceal a pregnancy, and the judicial court’s job to reveal the lie.

In his book, Farr wrote, “It is not uncommon for women of abandoned characters, or even married women, to conceal and deny their state of pregnancy.” So he laid out a series of proofs, broken into “certain” and “less certain” signs. Both categories are awful. His “less certain” signs include pretty much any ailment, discomfort or disease anyone has ever experienced, at anytime, anywhere. Vomiting, constipation, incontinence, headache, pain in the teeth, hunger, trouble breathing, swollen veins or extremities, and pains in the joints. Any of these meant she might be pregnant. Or a 72-year-old man. Maybe a dog who got into some chocolate?

However, if a woman had a swollen stomach with a pointy navel, a spongy womb opening (cervix) that was never conical or cylindrical, hard breasts, or halted menstruation, she was utterly pregnant. Farr doesn’t say that all or any of these must occur together. Any one of them is absolute proof, unless they can immediately be explained by another illness.

The examination for such a pregnancy—and for all of conditions of the female body—was to be performed by a male physician. Never a midwife, who as we have seen, are ignorant and easily deceived. (Or, perhaps what physicians saw as a midwife’s gullibility was actually a deeper understanding that when you’re dealing with the firmness of a breast or the shape of a cervix, there are few absolute truths.)

Anti-Rape Acrobatics

In 2012, Representative Todd Akin made an ass of himself in front of the nation with his assertion that a woman’s body would shut down a pregnancy if the conception occurred during a legitimate rape. He was roundly shamed, but he’d be glad to know that there was a time when learned men of medicine agreed with his sentiments. (Of course, they also believed that they could revive a drowned victim by forcing tobacco smoke up his rectum, and that urine was an excellent treatment for sore eyes.)

Elements of Medical Jurisprudence devotes a chapter to the crime of rape that was actually a chapter on how women lie about being raped. And it is brutal. Writes Farr:

In the consideration of rapes, three objects of attention present themselves.

1. Whether a rape, strictly so called, be possible?

2. Whether a woman, upon a rape being committed, become pregnant?

3. What are the signs of a rape being perpetrated?

In a book where you’d only expect to read about #3, you’ll find it to be just a footnote to the first two “objects of attention.”

Farr explains that rape really falls into two categories, attempted and consummated. “Attempted” means a woman is attacked and “great force” is used trying to violate her chastity, but full penetration is never accomplished. This, Farr admits, can actually happen.

But actual rape, when the sexual act is fully completed against the female’s will, is impossible.

Rape is impossible.

That was the leading medical and judicial opinion at the end of the 18th century. The reasoning? Wrote Farr:

For a woman always possesses sufficient power, by the drawing back of her limbs, and the force of her hands, to prevent the insertion of the penis into her body.

Throughout Elements, Farr applied knowledge, however ancient and incomplete, that was appropriate for his time. But when it comes to rape, he and Faselius became lazy and indifferent, ignoring countless considerations that applied just as well in 1787 as now. He ignored the fact that a women might be threatened with death if she doesn’t comply. That she may be too busy fending off blows to cover the entrance of her vagina with both hands. That she may tire before the man does, and become too weak to perform and maintain the anti-rape yoga position Farr seems to think her capable of.

Also, should a pregnant woman approach the court and claim she was raped, her condition is proof that she had wanted sex. Says Farr, “It may be necessary to enquire how far her lust was excited, or if she experienced any enjoyment. For without an excitation of lust, or the enjoyment of pleasure in the venereal act, no conception can probably take place.”

And so, in a way, Mr. Akin did have medical support for his claims. In the books these politicians might prefer us to be using, what he said is still science.

You Will Know Them by Their Vagina Wrinkles

Since rape doesn’t actually exist, one would think Farr would not need to explore the medical presentations of it. But he does, because occasionally rapes are committed upon small children who are not able to throw off their attacker. The most obvious signs, blood, trauma, swelling, and inflammation in the vaginal area, are by themselves proof of nothing, he reminds. Because such symptoms would happen just as easily if consent was given. (The age of “consent” at this time was between 10 and 12 years of age, by the way.)

So the best way to prove that someone’s lying about rape is to examine their genitals, after which you can visually discern if she “hath accustomed herself to venereal (sexual) habits, and of consequence is less to be believed upon a deposition of a rape.”

The tell-tale signs of a woman who’s had too much sex to be raped include:

-The lips of the pudendum are flaccid and distended more than that of a maiden.

-The clitoris is enlarged, and hath a prepuce which covers the glans arising from constant friction.

-The nymphaea (labia minora) are also enlarged, and are of a lighter and more obscure color.

-The orifice into the urinary passage is more open and exposed. This is owing to the flaccidity of the labia.

-The vagina is large and spacious.

-The wrinkles [of the vagina] are less prominent.

These symptoms, besides being re-goddamn-diculous, are all before/after observations. The immediate question is, how can the good doctor presume to know how spacious and wrinkly a lady’s vagina was before she claimed rape?

A Certain Class of People

The worst thing about Elements is knowing that the men who wrote it weren’t stupid or evil. They advocated radically positive ideas, such as that the disabled should be treated like normal people. They tear into superstitions about infertility and pregnancy, and insist that epilepsy is a real disease that has nothing to do with possession by demons. The entire last chapter is about implementing surprisingly modern measures for public health (you can’t just lay that plague corpse anywhere, you know, and expect to keep a healthy city).

So why did they think so little of women? Where did their logic and compassion go when an impoverished 16-year-old stood in the docket and admitted yes, she had been pregnant, but it had been a rape she’d been too ashamed to tell anyone about. That’s why she hid the pregnancy! As the girl herself was malnourished and sickly, the baby had come early, too young to survive! She had hid the body out of terror, but she had not killed it! Why was it the immediate reaction of all concerned to prove her a liar?

Perhaps Dr. Farr did not lack empathy so much as familiarity. No woman in his social class would ever be in that docket, not in 1787. The women he knew—the women the educated lawyers and judges knew—probably really were at a markedly lower risk for both violence and consensual extramarital sex, too. They were constantly chaperoned and tended, sheltered and kept in what was considered an endearing ignorance.

Their chambermaids and scullery girls were not so lucky. An exhausted 14-year-old girl carrying slop buckets out to the privy in the dark of night might meet with any horrible danger. But Dr. Farr would not have easily seen her, grubby, uneducated and forged by servitude, as a someone who could’ve been his daughter or sister. She would only be an inscrutable female, and thus a potential criminal.

If Your Life Depended On It

All of this isn’t to say that a woman on trial for her story in those days couldn’t have been lying. She might well have been lying, about anything or everything. Her life was on the line. If she were convicted of concealing a pregnancy before 1776, she was assumed a murderer and executed. After that date the law became significantly less severe, doling out prison if she was lucky and transportation to English-held colonies for forced labor if she wasn’t. This was very often its own death sentence. Who among us can know we wouldn’t lie to save our lives?

There’s no excuse for a person who lies about rape or who kills her baby. Even in 1787 there were Foundling’s Homes and religious institutions willing to take unwanted children. But these lies would have come from a place darker than what most women in 2015 can imagine. These women lived in a time where getting caught having sex was, at best, their personal ruination and, at worst, a slow death sentence. Humans have a survival instinct; lying is sometimes part of it.

So some women lied, let’s say. But let’s also acknowledge that sometimes they did not. Sometimes they were raped. Sometimes the child they intended to give to their married sister really was stillborn, which was very common in a world of sickly mothers and few medical interventions. And if they submitted their innocent bodies to legal inspection—the physician would likely find whatever he expected to find, since his evidence markers were fiction.

The problem wasn’t the liars. The problem was the consequences. In an effort to protect the innocent, the law set in place a system that was just as likely to destroy them. Allowances for unique situations were too difficult to pursue. It was easier to suspect women, to blame them rather than understand their position.

So women were confined to treacherously narrow paths. Falter in any way and you’ll lose everything. And even though ideas of rape, pregnancy and sex have changed in women’s favor over the centuries, the core problem still exists. Laws intended to protect end up being predatory, hurting innocents without differentiation. Where jurisprudence is concerned, a woman’s body is still not entirely her own. Changing that is the work of centuries.

Therese Oneill lives in Oregon and writes for The Atlantic, The Week, Mental Floss and more. She’s currently working on her first book, A Lady’s (Unspeakable) Guide to the 19th Century, available from Little, Brown in 2017. Meet her at writerthereseoneill.com.

Photos via Getty, scans via Internet Archive. Illustration by Jim Cooke.