The Long Shadow of the 'Welfare Queen'

In Depth

Image: AP

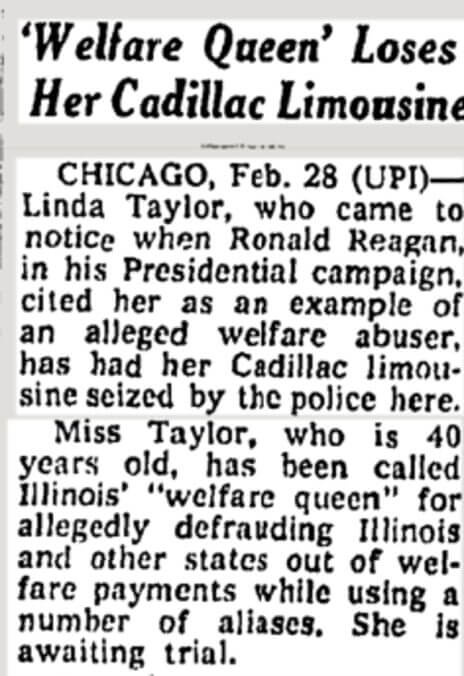

When Ronald Reagan and his advisors wanted to undermine the very institution of social programs, he turned to a news story out of Chicago—the tale of one Linda Taylor, who’d bilked the government benefits system out of so much money she was dubbed the “welfare queen.”

The trope of the “welfare queen” is powerful, toxic, and stubbornly persistent. Cemented by Reagan in his campaign for the presidency, the idea helped to both racialize and poison the very idea of financial assistance for the poor, a rhetorical trick that rendered everyone who applied for Aid to Families With Dependent Children benefits suspect by association. Even Joe Biden came to deal in the imagery, advocating for reform legislation in 1988 in the Newark paper: “We are all too familiar with the stories of welfare mothers driving luxury cars and leading lifestyles that mirror the rich and famous,” he wrote. “Whether they are exaggerated or not, these stories underlie a broad social concern that the welfare system has broken down—that it only parcels out welfare checks and does nothing to help the poor find productive jobs.” The words still have enough juice in the American consciousness that there’s a GLOW character who performs in the ring as “Welfare Queen.”

The term came to suggest an entire category of person. But originally, it was applied to a very specific person who did plenty of shit besides scamming checks out of the government, as Slate national editor Josh Levin makes clear in The Queen, his book about Taylor released earlier this year.

And yet, the concept of the welfare queen continues to reverberate down through the years, despite the fact that the program to which the term typically referred was essentially reformed out of existence under the Clinton administration. The very concept of welfare has been poisoned; you’ll notice universal basic income advocates opted for a technocratic term that carefully walks on the other side of the street. As we head into the 2020 election with primary candidates advancing arguments for attempts to create progressive programs that decrease the gap between the haves and the have-nots will have to reckon with her long, long shadow. Meanwhile, the Trump administration is sawing away at the food stamps program and, as The Guardian explored recently, the Treasury Department is still hounding women in their 70s and 80s who were allegedly “overpaid” government benefits decades ago. Our entire system of public assistance is punitive.

I talked to Levin for more on the history of the person and how she became the concept.

JEZEBEL: Who’s the queen of the title, and how does she get her crown, so to speak?

JOSH LEVIN: Linda Taylor was a woman who came to prominence and became a public figure in 1974, when the Chicago Tribune reported that she had been found by the Chicago police to be getting welfare under multiple different names. Within a couple weeks of that original story, the Tribune started referring to her as the “welfare queen,” because, according to the Tribune, she had stolen this huge amount of public aid money and was also driving a Cadillac. In the first article about her, they said she was planning a Hawaiian vacation and that she claimed to own a bunch of buildings on the South Side of Chicago. So the idea behind the name was that she was getting rich off of welfare, and that that was an outrage.

She becomes this symbol of anti-welfare sentiment. Did an existing narrative glom onto her, or was this built on this specific person of Linda Taylor?

I think it was definitely both. The prejudice against welfare recipients predated her, and if you look back, ever since the Aid to Dependent Children program (later Aid to Families with Dependent Children) was created in the 1930s, you can find stories about people getting money that they don’t deserve. But it was really around the time of the civil rights movement and the welfare rights movement in the ’60s and then into the ’70s that the popular perception of welfare became really racialized. The figure of the “welfare queen”—that term had been used a tiny bit before Linda Taylor, but it really came into prominence because of its association with Taylor. That was a term that came at a time when welfare was perceived by a large number of people in the US as a program that black people, particularly black women, were using to their benefit and these were the “undeserving” poor. It was an image that was adapted and transformed to fit with the times, but it wasn’t created from whole cloth to describe Linda Taylor. it was just that she was the right person at the right time—or the wrong person at the wrong time, depending on your sentiment. Just because, superficially at least, she so neatly fit all of the most pernicious and racist stereotypes about welfare recipients, about how they were getting rich while the ordinary taxpayer American was working hard and their tax dollars were going to somebody who didn’t work and was a cheater and all that stuff.

It is almost like if Ronald Reagan could have cooked her up in a lab, he would have.

I think that’s what you see in the way that Reagan told the story. Reagan did not invent her in a lab. Reagan was taking information that was publicly reported in news outlets that had good journalistic reputations. He was kind of cherry-picking facts and planting them in a particular way, but he found this anecdote, this one-off incident, and used it to extrapolate really wildly about welfare programs generally, about welfare recipients generally. Then he also just didn’t mention the parts of her story that were inconvenient. I think if her whole story had been told, it would have been a lot more clear to Reagan’s audience and everybody really that she wasn’t representative of the average welfare recipient at all. That she was this unique character that didn’t represent anyone or anything other than herself.

You make this point in the book, that the crime that becomes the national outrage is scamming welfare checks. You make a very convincing case she was a kidnapper, she was involved in multiple questionable deaths—but those were largely crimes against people of color.

Some of this stuff I excavated and it wasn’t publicly reported, but the fact that she was linked to kidnappings and the fact that she was accused of one homicide, that was all publicity reported, before Reagan ever started talking about her. So it was strange to me, as I started reporting, that Reagan could tell this version of her story that didn’t mention that, and that when the fact the fact-checkers of the 1970s wrote about Reagan’s claims, they didn’t even make note of it. They noted that Reagan was maybe exaggerating the extent of her fraud, because he would just quote numbers from state officials that said, oh, we think she’s stolen $150,000, or stuff that wasn’t actually proven, but people just suggested—Reagan would just quote it as if it was verified. But it just showed for me how overwhelmingly powerful the welfare queen image was, that it was able to drown out and overwhelm even accusations of kidnapping and homicide.

It was a different news environment, too. I feel like her story would play out a lot differently in 2019 for a huge number of reasons, but if some of this stuff was reported now, news spreads and proliferates instantly on social media or the internet more generally. It was easier for pieces of a story just to trail off or get eliminated along the way as it went from local to national news or it went from national news to political rhetoric. I think that’s what happened here. It’s really crazy that it did happen, but I think that’s what happened.

You look at so many archival stories or things where people are revisiting things from the past, it’s interesting to me how often it’s a question of frame—I think of many MeToo stories and how many of them the information was out there, but we see it differently with a certain perspective. It’s interesting how it’s all there, but people don’t put it together in the same way.

I think that’s right, and the fact that Reagan took up her story and that it got into this political factchecking machine, which we do really still have today, I think that really made it so that the truth of what she had done or hadn’t done became of lesser importance to the media, as opposed to the story of is Reagan telling the truth or is Reagan lying. And because her story is very complicated and not particularly congenial ideologically to anyone. If you want to prove that Reagan is a liar, it doesn’t really help your cause to say yeah, this woman is actually accused of murder! That’s why Reagan is a liar. That wasn’t anyone’s impulse, for understandable reasons. And then on the other side, when Reagan supporters believe he’s telling the truth or believe he’s being attacked unfairly, they’ll just try to firm up everything that he said and not go beyond it. That’s one thing I found in looking back at the reporting that was done about her case: Nobody seemed particularly motivated or interested in figuring out what this woman had done and where she’d come from and where she went after she was put on trial for welfare fraud. That’s what I hoped to do.

I thought it was really incredible the way that, without excusing her for the horrible things that she did, you explore her early life in a way that makes it very clear that she was treated in this deeply unjust way as a child and a young adult, she was a victim of the way America worked in the Jim Crow south. And I thought that was really compelling. But then she goes on to genuinely horrible stuff. It was very messy and interesting and very sad.

Yeah, thank you. I thought it was important to explain the context of what her life was like growing up and what life was like for people of color in the south in the first half of the 20th century. And it’s not to excuse her actions or even really to try to try to explain them, because it was important to me not to suggest causation and say because she was treated this way, this is how she treated other people. I think there is an impulse to play psychologist and to try to get inside her head. But in our conversation I’ve been critiquing the press and the way her story was handled, and because of that, I wanted to be really careful not to make claims that I felt like I couldn’t support. I wanted the book to be a factual account of what she did—what was done to her—rather than being a bunch of guesses about why she might have done things, when even the people who knew her really well told me, we didn’t really understand what she was doing or what she was doing it.

For somebody who was so chameleonic, “welfare queen” was the label that she couldn’t escape. That erased all of the complexity of her life.

So in that part of the book, I hope people got the sense and understanding that she was a human being. She was a person who had a family and her family did certain things to her and that surely must have affected her in some way. This is a person who had a history and a path through her life and charted this course through America. Without saying X happened and so then necessarily Y happened, my goal was just to lay out to the best of my understanding, these are the things she experienced and these are the things she perpetrated upon other people and let readers make their own connections and inferences about how the things may or may not have been connected.

She has this incredible complicated background and, as you’ve emphasized over and over again, she’s this incredibly specific person and had this incredibly specific journey, but then the way that she’s deployed is transparently a dog whistle and it collapses a specific person who’d done a specific set of things into this entire category of the welfare user.

Yeah, that’s right. And it’s interesting to think about that, given that she’s somebody who would adopt different identities herself. Like she would present herself as a heart surgeon or somebody who was a spiritual advisor or any of the various guises she put on to scam people or to worm her way into people’s lives, and for somebody who was so chameleonic, “welfare queen” was the label and that she couldn’t escape and that erased all of the complexity of her life. She was written about like she was a shapeshifter, right? Some of the first stories about her were about how she used race as a weapon. She would be Asian sometimes, or white sometimes, or black sometimes. And the welfare queen thing, it was so strong that it even erased her existence from earth. So many people thought that she just never even existed, that the welfare queen trope was just not based on a specific person, that Reagan had just made the whole thing up. But she did have this whole long precise and convoluted history that just kind of disappeared from the record.

She spins all these wild stories about herself to scam people and then she becomes locked into this incredibly specific racist narrative and then, once she’s done being useful, she’s phased out of the narrative. It implies there’s this entire universe of welfare queens.

Yeah, and there are stories written about, you know, “welfare queen has a successor,” whether it’s in Chicago or California. I don’t remember the headlines off the top of my head, but there are like plays on words around “welfare queen gives up her throne,” because this person has scammed $250,000. Once the trope has been established, she’s outlived her usefulness and other people come in and fill that role, and it just shows again that nobody was ever really interested in her particular story except to the extent that it was useful to establish this trope and political idea.

The damage that does is both huge in terms of how everyone who’s in any kind of social services program, especially women of color, it categorizes them as suspect just by virtue of being part of this program. People are seen suspiciously. But then, more narrowly focused on her and the damage that it does, after she’s put on trial, she’s sent to prison, and she gets out, it’s like nobody cares about her anymore and she goes off and there are two people that die suspiciously after that happens. Neither of those deaths are really investigated or connected to in any way. She was able to move through the world, sowing all this destruction, and whether it’s the press or law enforcement or politicians, nobody cares about at all. Just because it’s not politically useful or politically interesting.

I was wondering if you could talk a little bit abut how the narrative continues to influence politics. You mention this idea of the welfare rights movement earlier—it’s hard to even imagine, if you are going to advance an argument for a social program, say Medicare for All, anybody advocating for a right to something referred to as “welfare.” It’s like the whole term was poisoned. I was wondering if you could talk a bit about the long legacy of the trope?

Welfare becomes a pejorative term, and it doesn’t necessarily refer to anything specific. I think most commonly it referred to ADC or AFDC, just in common parlance. But really, practically, what welfare is is a social service program that benefits somebody else. It doesn’t benefit you. That’s again this category of the deserving poor vs the undeserving poor, and the people who are perceived to be welfare recipients are before, during, and, after the Linda Taylor story broadly seen as undeserving. So by the ’90s, when the Clinton welfare reform happens that ends AFDC, that “ends welfare as we know it,” welfare was unpopular in polling across every demographic group. It was unpopular with Democrats and Republicans, Clinton talked about it differently than Reagan did. He did not stereotype recipients in the same way. He was more talking about how the program didn’t work for the people who were on it, which in some ways was true, but the solution was to destroy the program. That’s what it ended up being, in practice.

It’s not like that ended the conversation. When NFDC became TANIF and it became this temporary program where there was a limited pool of money, it’s not like that was like all right, problem solved. The animus migrates, whether it’s food stamps or medical programs. It’s always a very powerful message, politically, to tell people that whatever problems that they’re having in their lives that there’s a specific category of people that’s to blame for it, and the people that often get the blame are the ones who are most vulnerable and don’t have as much of a voice in the political process, undocumented immigrants being the most relevant example in some ways today. You have people in parts of the country where there are very few immigrants being susceptible to the idea that their lives are worse because of immigration. It’s not really logical, but it’s powerful, and I think that’s why it’s going to persist forever.