The Deep Ties Between the Catholic Anti-Abortion Movement and Racial Segregation

In Depth

The video of MAGA hat-wearing Covington Catholic High School students, who were in Washington DC for the March for Life, in a tense standoff with Black Israelites and a Native American contingent from the Indigenous People’s March, has become hotly debated national news.

Though the close focus is on the immediate chain of events, it’s important to note the historical intersection of conservatism, race, and abortion that set the stage for the arrival of these white Catholic students. The modern Catholic anti-abortion movement was born in white enclaves and shaped by the politics of white flight and anti-integration activism. The sight of white Catholic teens wearing clothes emblazoned with Donald Trump’s racially inflammatory brand at the March for Life, marks a vital connection that has shaped modern conservatism and the Republican Party.

Racial politics undergirded the anti-abortion movement from the outset and continues to shape its imagery and concerns. The modern Catholic anti-abortion movement emerged in the early 1960s in response to heightened agitation by legal and medical organizations and mainline Protestant and Jewish groups for abortion law reform. Crucially, this organized anti-abortion activism was cradled and nurtured in white Catholic enclaves in and around Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Detroit, and New York City (among other places) and at the height of white flight. Covington Catholic High School is part of this history. The overwhelmingly white campus is mere minutes away but cordoned off from the predominantly black public schools of downtown Cincinnati.

In many instances, parishioners bucked their own religious leaders who advocated for racial justice.

After World War II, white Catholics increasingly moved from cities to suburbs. For those white working-class Catholics who didn’t leave cities, their neighborhoods often abutted African American neighborhoods. This proximity set the stage for explosive conflicts over school busing and integration of public and parochial schools. In many instances, parishioners bucked their own religious leaders who advocated for racial justice. There are newspaper reports, for example, of white parishioners heckling and shouting down nuns who sought to integrate Detroit’s Catholic schools in the early 1970s. Many other Catholics quietly and unceremoniously voted with their feet by moving deeper into all-white suburbs and exurbs. These parents espoused a colorblind logic—many disavowed racial motivations altogether—and instead emphasized the need for safer schools and neighborhoods or lower taxes. As these white Catholics migrated away from black people, the Catholic Church followed and built churches and schools in these neighborhoods. The Catholic Church, in other words, practiced and preached racial justice even while buttressing racial enclaves and de facto segregation academies.

Whether it was in cities or suburbs or through race-blind or explicitly racist logic, white Catholics resisted integration through the 1960s and 1970s. And at this very moment of racial retrenchment, abortion became increasingly important to Catholics, as well as national politics. Catholics had long officially opposed abortion. But with the rise of organized abortion rights groups across the country in the 1960s, the Church began marshaling considerable resources and mobilizing its faithful to oppose legalization. Unsurprisingly, the racial animus and colorblind logic that underpinned white retrenchment also shaped parishioners’ anti-abortion activism.

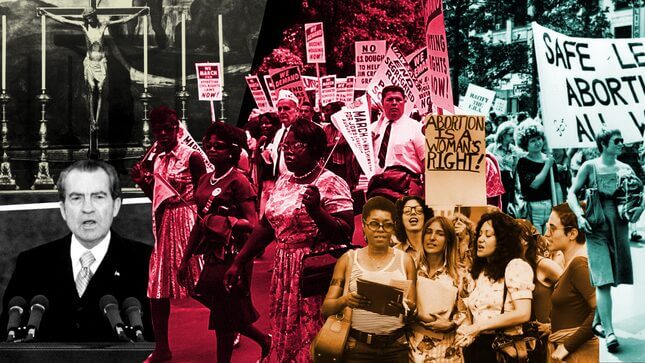

By 1972, Richard Nixon was running a reelection campaign that was fueled by racist dog whistles to white Southerners and to white urban and suburban Catholics. Nixon’s strategist and speechwriter Patrick Buchanan explained how the 1972 campaign sought to “drive a wedge right down the middle of the Democratic Party,” with messages that targeted Catholic voters “who fight against abortion in their legislatures, who send their kids to Catholic schools, who work on assembly lines… or who have headed to the suburbs… they are where our votes are.”

As abortion and resistance to integration took center stage nationally, it played out among the white Catholic voters in Michigan with special force. Michigan voters were roiling over attempted school integration plans. The Democratic primaries had already highlighted white discontent with the victory of segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace. Adding fuel to an already fiery politics was a statewide referendum on whether to legalize abortion.

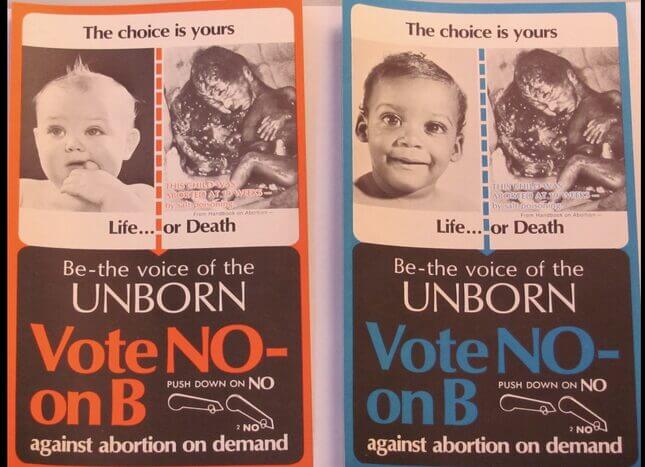

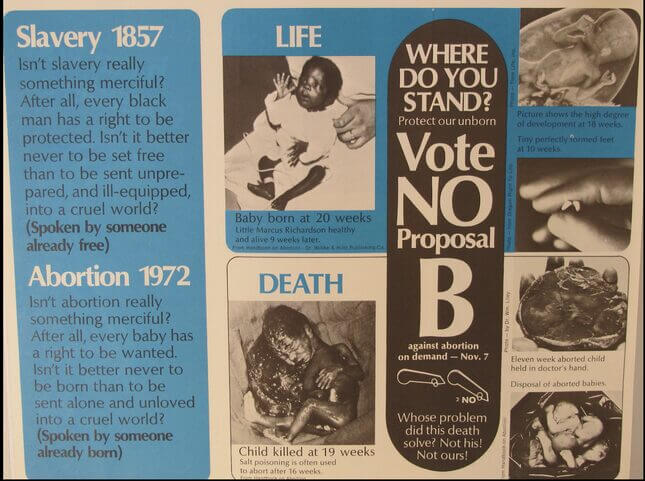

The abortion referendum—known as Proposal B—was shaped by this racially charged backdrop. Through the fall of 1972, Michigan’s white Catholic anti-abortion leaders courted African American support. Polling told them that they needed black votes to win, but racial tensions were so high that Catholic abortion leaders literally segregated their anti-abortion campaign.

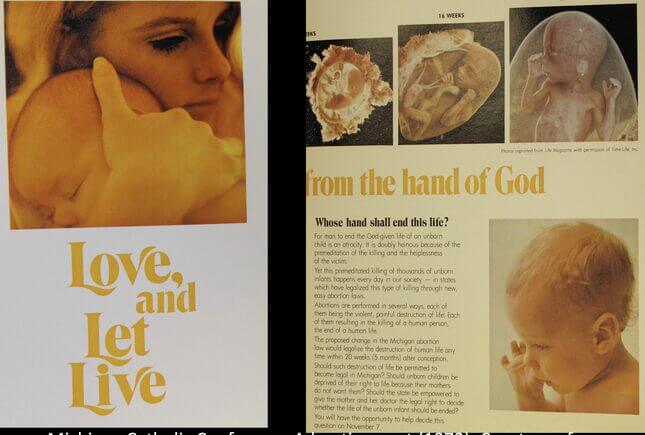

Anti-abortion activists produced one set of images featuring images of black babies for African American voters. They produced imagery with white babies for white and black voters alike. The reason? Much of the literature directed toward the black community described abortion as black genocide. And white activists had seen up close the depth of anti-black animus among white Catholic voters. Campaign organizers feared that if white Catholics saw images of black babies in anti-abortion campaign literature they would come to support abortion.

At the same time, anti-abortion campaign literature emphasized images of white mothers holding white babies. Images of black mothers, however, were completely absent. This editorial choice implicitly spoke to the ways in which white voters viewed black mothers as welfare queens and baby-making machines. The visual ghettoization of black people in anti-abortion literature, in other words, coincided with and reinforced the actual ghettoization of black people through Catholic opposition to integration.

Richard Nixon won decisively in Michigan and a record number of Catholic voters supported him because of his opposition to school integration and abortion. Needless to say, conservative Republicans paid close attention. In the aftermath of the 1972 election, anti-abortion and anti-integration politics yielded dividends.

Nearly half a century later the image of white Catholic young men professing their faith, marching against abortion, and doing so while wearing their support for Trump on their bodies, underlines the conservative capture of white Catholics. Anti-abortion politics remains a bulwark of the Republican Party. Appeals to white racial resentment continue to shore up support for Trump. And slogans like “Make America Great Again” encapsulate conservative nostalgia for an older racial, gender, and sexual order. The political and religious expression of these young men could not help but mark the historical intersection of Catholic anti-abortion activism and white conservatism.

Longstanding racial scripts set the stage for the March for Life and for the confrontation at the Lincoln Memorial this weekend.

The readiness with which Americans identified these young men as racist didn’t just come from MAGA hats or racist taunts. Longstanding racial scripts set the stage for the March for Life and for the confrontation at the Lincoln Memorial this weekend. Americans are not blind to the 50 years of racialized and sexualized conservative messaging toward white Catholic voters. White Catholics, meanwhile, have built suburban walls around themselves and their schools, have become keystones of the conservative movement, and opposed abortion using imagery that showcases endangered white babies and their white mothers.

History gives meanings to seemingly individual confrontations just as it sets the terms for broader political conflicts over sexuality and race relations. A chance encounter at the nation’s capital between white Catholic young men, African Americans, and Native Americans made visible, for a moment, a larger history of religious, sexual, and racial debates that have shaped modern American politics.

Gillian Frank is co-host of the “Sexing History” podcast and a postdoctoral research fellow at University of Virginia’s Program in American Studies.

Subscribe to his podcast, Sexing History, on iTunes. To listen to an episode where Sexing History explores the racial politics of abortion, click here.