Reading Judith Krantz in the Age of Donald Trump

In Depth

Illustration: Elena Scotti

Reading Judith Krantz is like running errands around town in a Lamborghini driven by somebody coked to the gills and very, very bad at figuring out the most straightforward route, but the running gossip monologue is so entertaining it distracts from the fact that you’re careening through every single red light.

That is to say, Krantz is precisely my kind of writer. Krantz, who died on June 22, wrote highly popular commercial fiction that encapsulates her era, the late 1970s to the mid-1990s. They are also some of the most sexually fantastical bestsellers ever written. (E.L. James could never.)

But, turning to her novels in the wake of her death, I expected her depictions of the ethically lax, sexually prolific rich and famous would be yet another formerly enjoyable thing poisoned by the ascendence of Donald Trump—particularly because, in addition to her hugely successful first book, Scruples (1978), Krantz’s I’ll Take Manhattan features a heroine who lives in Trump Tower. The tower is less a location than an opportunity to muse on the limitless potential open to a wealthy woman in New York City: “She was filled with glee, the kind known as unholy. Manhattan belonged to her! She must be the only person away this early, the only person with this view, that had been carved out of the sky…. Maxi realized how lucky she was to possess a view that altered the spirit.” Does she, though?

Krantz’s books are often dismissed as trash, but as any archeologist will tell you, there are few resources so valuable as a nicely overflowing dump.

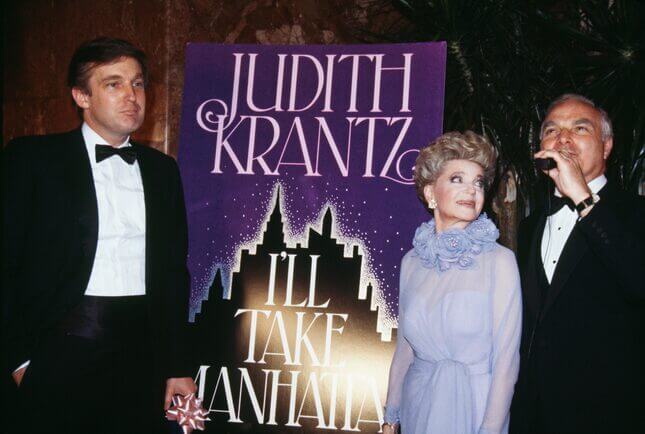

Naturally, the Donald makes an appearance and was featured even more prominently in the promotion for the book. The book’s black-tie release party was held at Trump Tower and Trump himself presented Krantz with a key to the tower—gold, of course. And when he appeared in the 1986 miniseries adaptation, the New York Daily News declared: Donald Trump a Natural at Playing Donald Trump,” a headline that now sends a chill down the spine. And yet, upon a 2019 read, these books retain their iconically poolside appeal, dissolving the rest of the world in the low-stakes troubles and misadventures of lightly sketched stock characters.

They are also a valuable time capsule. Krantz’s books are often dismissed as trash, but as any archeologist will tell you, there are few resources so valuable for reconstructing a historical era as a nicely overflowing dump. Krantz’s books are a perfect depiction of the cultural moment that gave Trump his start, the social universe that nurtured him as a young real estate developer puffing himself into a national brand that would allow him to continue pulling down the dollars through licensing fees and reality television long past his prime as a businessman.

For example, there’s a character in Scruples, a TV reporter on the movie industry, whose career resembles that of Rona Barrett, a celebrity journalist who was maybe one of the first people to ask Trump whether he saw himself with a future in show business. Another example: Krantz met her husband, Steve, at a party thrown by her high school classmate Barbara Walters—who, of course, was friends with the man who mentored Trump, Roy Cohn. In her memoir, Sex and Shopping, Krantz tells a story about her husband wandering around Paris, trying to find out the Super Bowl score before she suggests they try asking the concierges at the Ritz. “We’d found our Parisian hotel after years of looking for one,” she announces happily.

It’s a perfect depiction of the social universe that nurtured him as a young real estate developer puffing himself into a national brand.

Scruples and I’ll Take Manhattan are, quite literally, about the rich getting richer, or at least the rich becoming more successful and famous and therefore personally fulfilled (while staying just as rich). But even as Krantz writes with forgiving fondness, this new wealth is also seen clearly, as a bunch of vulgar assholes with hardly any scruples and moral compasses frequently on the fritz. (That’s the whole point of the name!) And there’s something refreshing about the glibness with which Krantz treats these people, especially reading her books in an era in which the super-rich are so ridiculously smug and serious about their contributions and their “wellness” routines and trips to fucking Davos. Oh, the panels, the endless self-congratulatory panels! Krantz would have had a good line about those goddamned panels.

Take Maxi Amberville, the heroine of I’ll Take Manhattan, for example. The book knows that she’s basically a spoiled brat, even as the book is somewhat charmed by her antics. Getting something like a real job—launching an instantly successful magazine to spite her vindictive uncle—transforms her into an adult, but the book is nowhere near as smug about this as your average empowerment feminist #girlboss fairy tale. Objectively, Maxi is, like Ivanka Trump, using her massive resources to carry on her father’s legacy, but everyone around her, including a number of people who genuinely love and support her, are driven absolutely bananas by her ridiculous behavior. (She is a magazine editor, after all, in an era when they were larger than life.) Then again, it’s refreshing to read novels where the rich are so clearly and frankly depicted as vulgar and trashy and utterly without scruples. We’d all be better off if Ivanka and Betsy Devos and the rest of Trump’s lavishly wealthy flunkies would just launch clothing stores or spend their time on yachts screwing around on each other, and get out of our lives.

It’s astonishing to consider how much farther we’ve crawled, as a culture, up the asses of rich women.

These books are a document of the 1980s—a decade absolutely enamored of money and material excess—and yet, it’s astonishing to consider how much farther we’ve crawled, as a culture, up the asses of rich women. Meanwhile, Trump has come to take himself the most seriously of all, reportedly trying to arrange for the inclusion of tanks in the backdrop of his July 4th address to the nation.

I don’t need to tell you that these books are full of the casually offensiveness of their era. Billy starts out as a love-starved fat child, and the condemning descriptions of her weight are relentless. Particularly shocking are the ways Krantz writes about gay people in Scruples; one of her secondary heroines, Valentine, gets her heart broken when she is used by the owner of a fashion line to prove he isn’t homosexual. (Krantz used this plot line, by the way, as a way to include a cruising scene involving a glory hole.

Krantz relies on flashbacks so heavily and so chaotically that I could barely keep straight where I was in the timeline. It’s 1976! It’s 1937! It’s 1968! It’s 1954! It’s 1976 again, and the main characters are only just now finishing the conversation that opened the book!

But in her hands, this feels propulsive rather than confusing. The structure works in her favor, allowing a reader to forget what any character was doing 15 years ago and just go with it when they suddenly pivot to some new ridiculous adventure. For instance, Billy Ikehorn in Scruples begins her life as a Bostonian poor relation, goes to Paris for some finishing, has a brief tour of duty as a secretary in New York City, marries an outrageously wealthy, much older man who spoils the hell out of her, has a string of affairs with his male nurses after he has a debilitating stroke, founds the high-end boutique Scruples for fun, hurriedly marries a movie producer after a trip to Cannes, helps him save one of his movies from a vindictive studio head, and finally gets knocked up. Got all that? If you don’t, the important thing to remember is that this is all basically a setup for Krantz to do a Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous-style tour of glamorous settings of the 20th century, a style that must have come easily to a former star writer for Helen Gurley Brown’s Cosmo.

Rereading Krantz gives the feeling of awful foreshadowing, which Elizabeth Schambelan described in an essay at the LA Review of Books: “I expected to feel amusement and nostalgia, but what I felt instead was slow, creeping, horror-movie dread, as the conviction dawned that some kind of cackling clairvoyance was at work — that Krantz was an oracle who had offered us a glimpse of our destiny, if only we’d had the acuity to see it.” There’s a moment in I’ll Take Manhattan where Maxi’s wicked uncle twists the screws as part of his plan to destroy his brother’s magazine empire: he tells the company’s money man to begin cutting costs deeply in order to jack up profits for a forthcoming sale, to get better terms. He’s doing it explicitly to destroy the magazines, which horrifies the other characters. Three decades later, and the world has basically been wrecked by firms taking this short-term approach to profits for purely financial reasons, rather than anything so comparatively charming as a villainous quest for revenge. I’ll Take Manhattan is a romance about the difference between the money men and the people with money and some sort of true artistic spirit. Of course, the last thirty years have proven that it’s all about the bottom line in the end.

Rereading Krantz gives the feeling of awful foreshadowing

What’s striking, too, is how utterly Krantz’s particular fantasies of wealth have fallen out of fashion, even as we are living through a decidedly grim version of their realization. The billionaire man is still a powerful figure of fantasy—Christian Gray has made a lot of money for E.L. James and for Hollywood. But Anastasia was a middle-class kid fresh out of college, and the romance was explicitly tied to the closing of their enormous class gap. It was about a girl lifted to rarified, financially flush heights, rather than a woman scheming her way up some ladder. Even in a world dominated by the likes of Sheryl Sandberg, the Krantz model, the Dynasty model of the sexy blockbuster fascinated with the doings of larger-than-life, glamorous rich women no longer seems to hold the same appeal.