I'm Obsessed With This Victorian Crime Anthem: 'Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away'

In Depth

Apparently, one of the hottest songs of 1840 was a ballad, a jaunty little bop that waxes poetic about a life of crime and basically translates to: “Keep Robbing, Boys!”

This fact comes courtesy of Murder by the Book, the latest by the knowledgeable Claire Harman, who has written biographies of Charlotte Brontë and Jane Austen. It’s short and enthralling, turning an 1840 murder that horrified London into a page-turner that can hold its own with any one of the many murder-minded podcasts out there. The book unpacks just why the violent stabbing of Lord William Russell—in his home, under such circumstances that it seemed increasingly likely it must have been one of his servants—so thoroughly rattled Britain and particularly its elites. It was the era of the Chartists, a mass movement for working class power, and the aristocracy was already nervous; several lords would attend the eventual trial personally.

As part of unpacking the crime, Harmon takes readers on a journey through the early Victorian literary landscape and specifically delves into a controversial subgenre: the “Newgate novel.” Books were cheaper than ever and literacy was growing; the resulting mass audience loved sensational stories of crime and derring-do. Early successes “spawned a whole school of criminal romance, known disparagingly as ‘Newgate novels’ after the grisly catalogues of crime and punishment that inspired them in The Newgate Calendar; or, Malefactors’ Bloody Register (first published in 1773)—violent, intriguing and thoroughly addictive true-life cases,” Harman explains. These books were all loaded up with “flash cant,” a type of slang apparently derived from Romany and associated with criminals—though you wonder how much of it was the work of novelists.

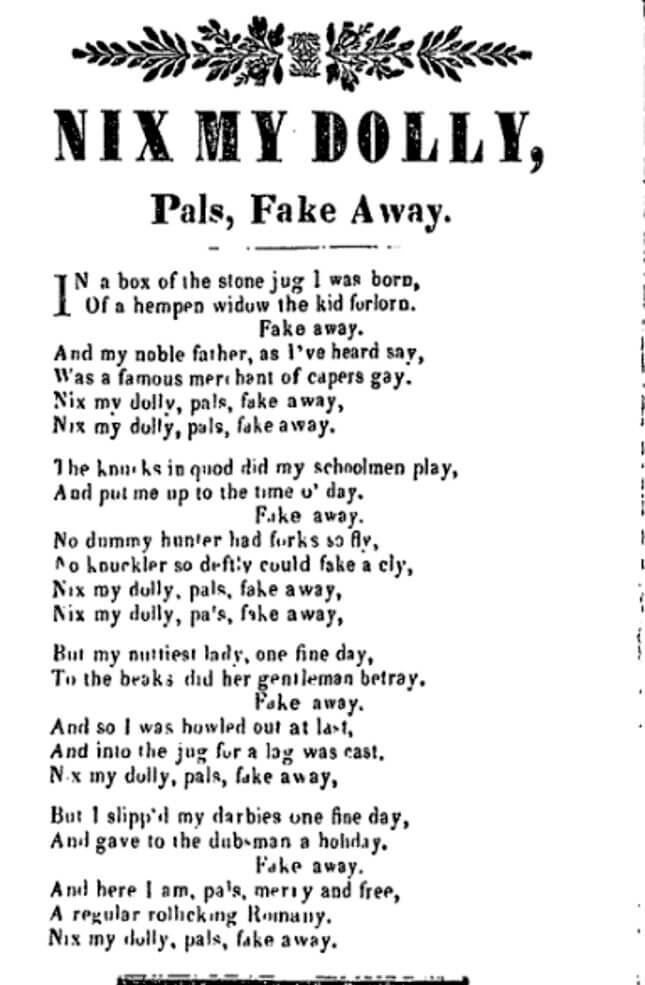

Perhaps the most successful of these novelists was William Harrison Ainsworth, who hit it big with Rookswood, in which he created “a purely flash song,” “Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away,” whose “great and peculiar merit consists in its being utterly incomprehensible to the uninformed understanding.” And it is that—here’s the song in all its bewildering glory from the Bodleian’s website dedicated to broadside ballads, a magical place in its own right:

There’s a slightly easier to read version here. You can hear the tune yourself in this YouTube video of an antique music box; it’s easy to imagine a rousing rendition in a beer-soaked public house.

Ainsworth followed Rookswood with the even more popular Jack Sheppard, which was quickly adapted into plays all over London (copyright being a disaster at the time) and most successfully into a musical that borrowed “Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away” and made it into a proper hit. Harman quotes a contemporary who says it was “as popular in the drawing-rooms of St. James’s as the cellars of St. Giles’s, whistled by every dirty guttersnipe, and chanted in drawing-rooms by fair lips, little knowing the meaning of the words they sang.” Or maybe they did, and that’s what was fun about it.Newgate novels were already controversial, stirring up concern about the prospect of tempting the “lower orders” into a life of crime, threatening the property and even lives of the elites, at a time when they were already concerned about the Chartists and the overall unsettlement of the social order wrought by the industrial age. The murder of Lord William Russell—whose valet would eventually confess, blaming Jack Sheppard for putting him on the path to ruination—would set off an outright moral panic that recalls Tipper Gore’s crusade against violent rap lyrics and reminds us that every single fight in popular culture has a longer history than is generally acknowledged.

The genre would fall dramatically out of fashion; Charles Dickens would revise Oliver Twist again and again, making it less and less typical of the form. Literary crime coverage was “gentrified,” as Harmon puts it, in the form of the burgeoning detective fiction genre. No more elevating criminals—if you wanted to write about fictional vice and disorder, you had to do it in the context of a story about some upright citizen uncovering the truth and restoring the proper social order. Increasingly, if you wanted gruesomeness, you turned to newspaper coverage.

Makes you wonder what they’ll say about the proliferation of true crime content in a century.